The full heat of the Japanese summer is gone, the deep blue skies, boiling white cumulonimbus clouds and the cacophony of cicadas. But the heat remains, provoking sweat and the desire for shade. The hiking boots have been cast aside for a new pair of hiking sandals. I’d stuck with the hiking boots because I was sure they wouldn’t cause blisters. How would the sandals fare?

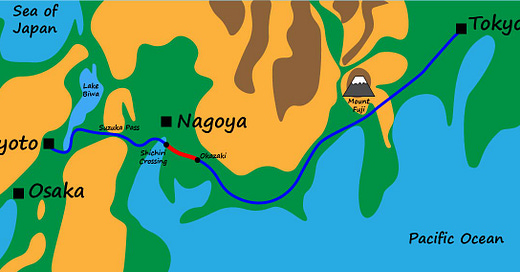

I’m now far enough from Kyoto that it’s worth taking the shinkansen to Nagoya, and making my way to the other side of the shichiri ferry crossing from there. The crossing point is marked by a reconstructed lighthouse in a slightly shabby park. An old man, spotting my ground mat concertinaed on the bottom of my rucksack, invites me to lay it out on a bench and relax. No, no, I’m just starting, I haven't done any walking yet! What had been an open sea crossing across Ise Bay was now a confluence of rivers between reclaimed land containing yet more suburbs and a factory making aluminium parts for cars.

I take some photos, read about the history of the area, and set off along more “heritage brown” streets towards the tree-covered rise of Atsuta Shrine. This shrine, also known as Miya, is one of the most important shrines in Japan due to its housing of the imperial regalia sword - Kusanagi. The sword has a history that goes far back to Japan’s earliest mythology in the Kojiki, but strangely, almost nobody has ever actually seen it, and it isn’t on public display.

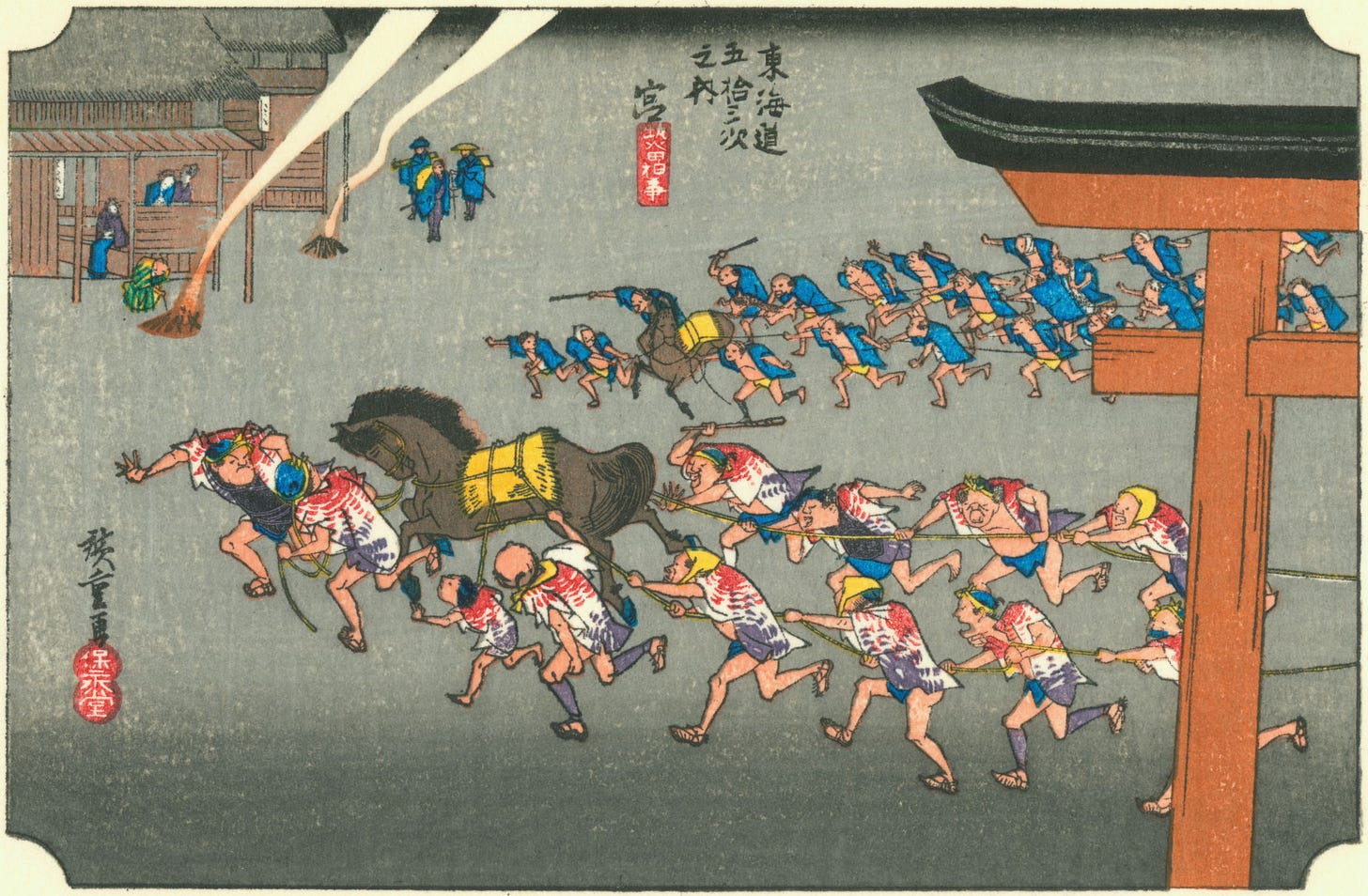

Hiroshige’s print of the shrine shows an annual horse festival held on the 5th of May each year. Competing groups of villagers, wearing tie-dyed hanten (short winter coats) from Arimatsu, are urging their horses on in a race to somewhere, while a sparse audience of travellers look on past small night-time bonfires.

Beyond the shrine, shabby housing surrounds canals. There is nothing in particular about Nagoya that makes it feel different from any other Japanese city here. As I cross a bridge to leave the Atsuta district, on my left is the Paloma factory, and shortly after, the Paloma headquarters. Paloma is a company worth looking at, it makes gas konro stoves that nearly every Japanese household has. People rarely have ovens with stoves on top in Japan. Its main competitor in the Japanese market is Rinnai, with around forty percent of the market, which is also headquartered in Nagoya. Paloma’s market share has declined in recent years, to less than twenty percent, following a scandal involving its water heaters. Sporadic incidents of carbon monoxide poisoning due to malfunctioning exhaust fans occurred from 1980 onwards, but nobody connected the incidents at METI (the ministry of trade and industry) until 2006, when a recall order for the potentially faulty water heaters was issued. Paloma owns Rheem, a manufacturer of water heaters in the United States. Looking at the market shares of water heaters in the US and Japan, the concentration of the top manufacturers is very similar. It’s a similar story if you look at the gas stove market share in Japan. I can’t see where the hyper-competitive domestic industrial structure is that

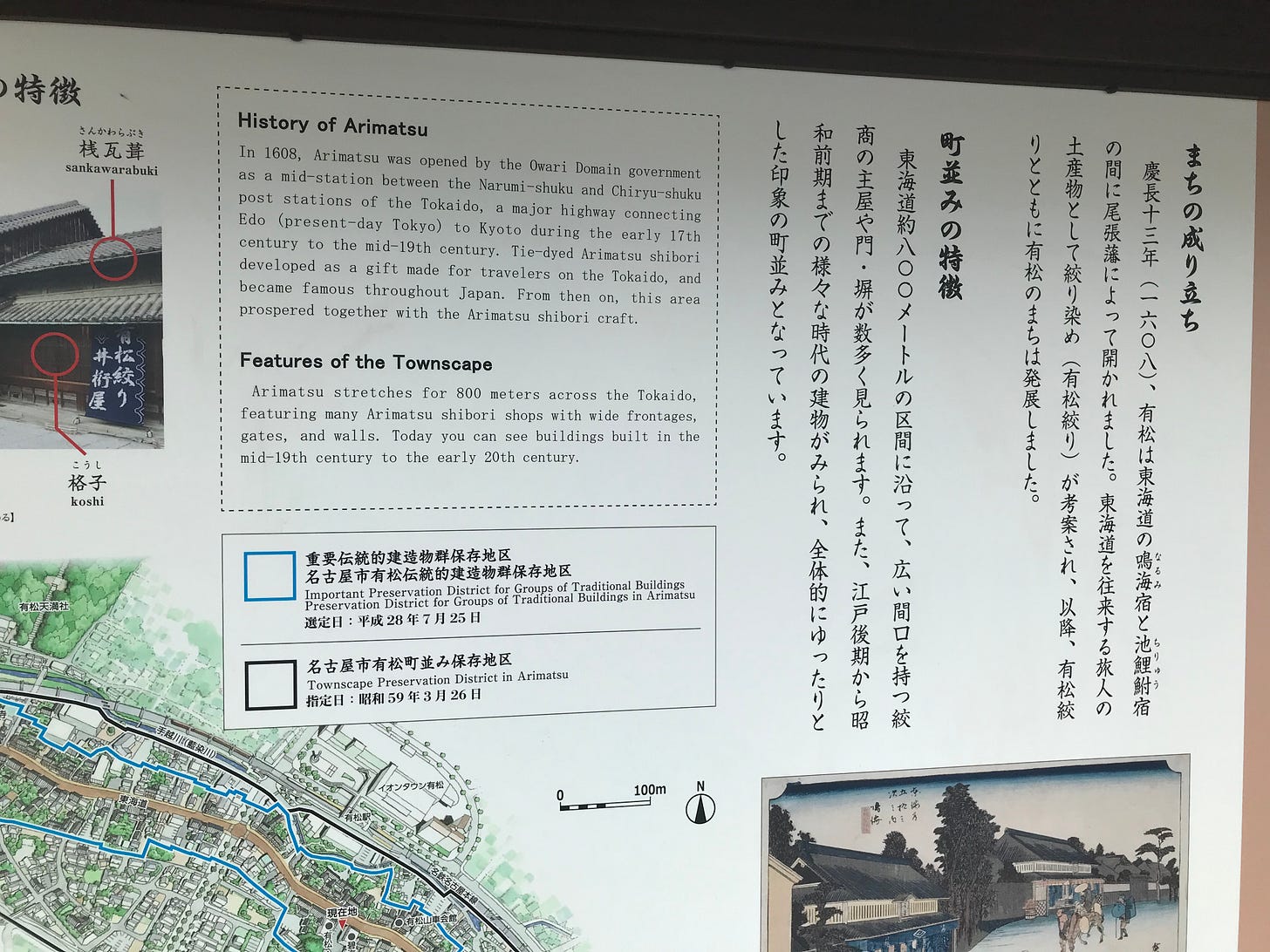

describes at , outside of a few select industries.Shortly after passing Paloma’s factory and headquarters, I pass Brother International Corporation’s headquarters, one of those Japanese companies whose names you would never know were Japanese. Named after the Yasui brothers who started it, as a sewing machine manufacturer, somehow the Yasui part of the name was dropped. After this, I passed through Narumi-Juku, which is the next print in Hiroshige’s series. There’s nothing much left here, but a little farther up in Arimatsu, a whole street has been preserved, despite its proximity to a major highway.

Before I get to Arimatsu, I pass one of the best preserved ichirizuka distance markers along the Tokaido. The tree atop the mound is propped up and surrounded by bamboo mats. To find such a well preserved tree and marker in the middle of a modern housing estate is pretty amazing. I was expecting the best preserved ones to be out in the countryside somewhere.

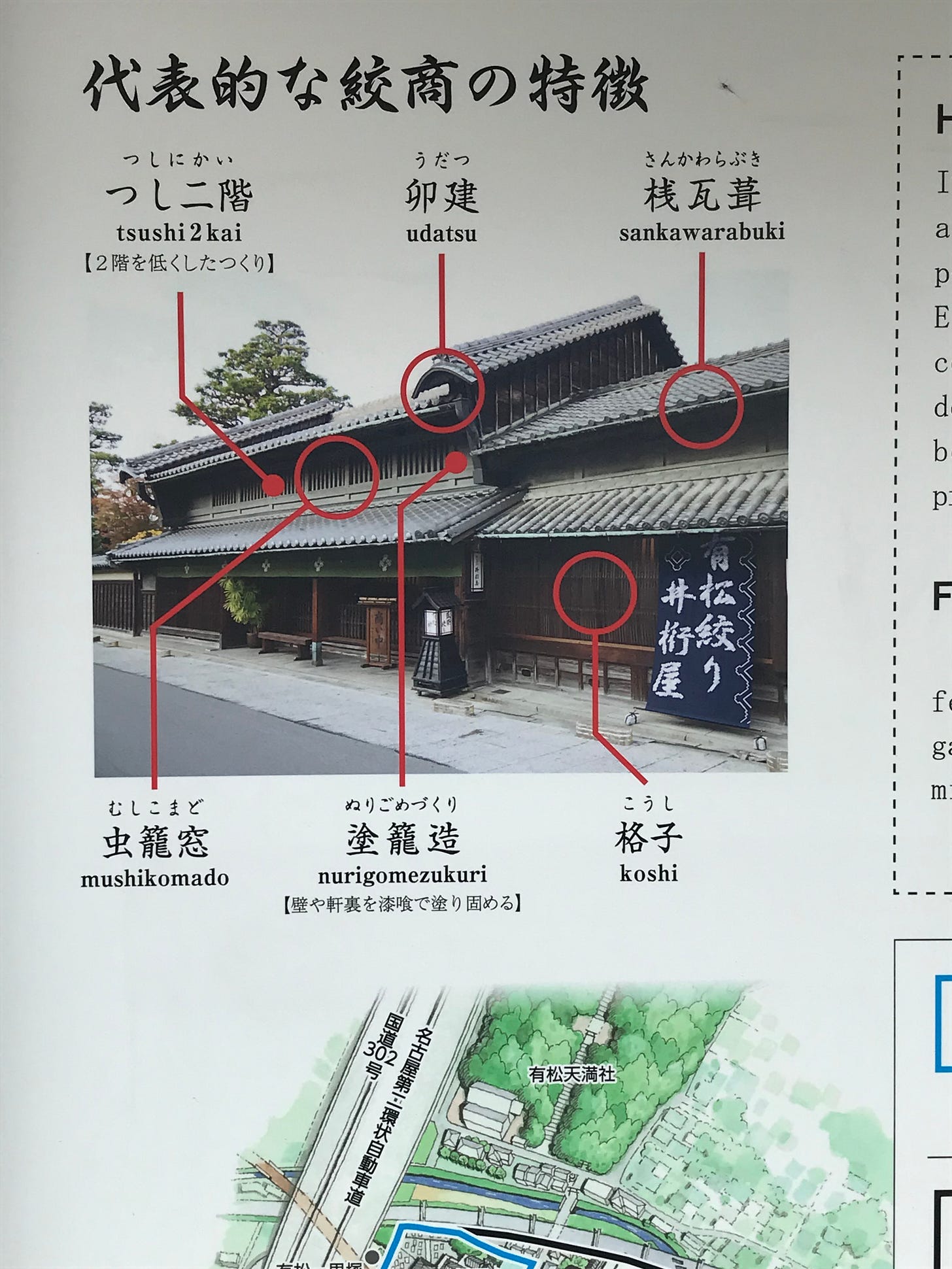

Arimatsu is the home of a type of large-pattern shibori (tie-dye). Shops selling this can be seen in Hiroshige’s print. The same type of two-storey building with nurigome thick fire-proof pillared second storey can be seen today, and the area has made the most of its tie-dye history with a lot of souvenir shops selling every kind of tie-dye goods imaginable. I guess this street would normally be packed with tourists, but mid-pandemic it’s deserted.

In 1560, one of Japan’s more significant battles was fought near Arimatsu at Okehazama. Imagawa Yoshimoto, a warlord from Shizuoka attempted to seize the imperial capital at Kyoto by moving his huge force of 25,000 troops south along the Tokaido. Oda Nobunaga, who would later go on to help unify Japan, tried to block his progress as Inagawa’s troops crossed his territory. Nobunaga could only muster a small force of 2,500 troops in the short time he had. He stopped to pray at Atsuta Shrine, then surprised Imagawa’s force at Okehazama, while Imagawa’s troops were drinking sake in celebration of victories over some of Nobunaga’s smaller castles. One of the hostages released after Inagawa’s defeat was Tokugawa Ieyasu, who would go on to become Shogun and properly unify Japan.

By now, the heat is really building. I’m bathed in sweat and my sandals are chafing. A McDonald’s in a dingy shopping centre gives me some respite for a couple of hours. I feel acutely conscious of my foreignness, an out of town foreigner, trying to look at my Tokaido guidebook (yes, I have one now), and massaging my feet surreptitiously under the table.

I finally hit fields, the edge of Nagoya! It’s taken more than half the day just to leave the city. The Sakai (boundary) River is a fitting exit from the industrial suburban slog. On the far side of the river is Pasco’s industrial bakery. Pasco is a bakery company that fills every convenience store in Japan with their bread products - including English muffins! I’m not sure corn grits really belong on English muffins, but they’re pretty good anyway. A quick dive into the Japanese bakery industry reveals incredibly skimpy profit margins. The gross profits (what it actually costs to make the bread products) are reasonable, but the operating profits are miniscule. Pasco, even in a good year, only has a one percent operating profit margin. In a bad year, it’s only 0.1 percent. Even the industry leader - Yamazaki Bread, only makes just over one percent operating profit. Why such pathetic margins? The US seems to have average operating margins of around ten percent in the food processing industry. I’m not sure, but I’m hazarding a guess that Yamazaki, Pasco et al are desperately trying to maintain their market share without raising prices, and advertising and distribution costs eat up a big chunk of their gross profit margin.

Pasco was founded in 1920, two years after huge riots swept across Japan. Japan might be a peaceful and law-abiding country now, but it wasn’t always so. In 1918, protests over the price of rice for labourers spread from rural Toyama prefecture to the rapidly industrialising city of Nagoya. About a quarter of Nagoya’s population were estimated to be involved in these riots (and remember about half the population were children at this time). It took ten days, some heavy policing, and the promise of a halving of the price of rice to quell the riots. In the aftermath of these riots, it was clear that Japan would struggle to feed its growing urban population on just domestic rice production alone. Imports were going to be needed, but China was in turmoil at the time, so there was little possibility of importing rice from there. Step in bread - at first the food of choice for the metropolitan urban elite - companies like Pasco would help to make it popular with the masses. Rice exports for troops in the second Sino-Japanese War further exacerbated the shortage of rice, and wheat products began to expand to fill the gap. After World War Two, the American occupation government started a programme to provide school lunches to ensure schoolchildren got at least one substantial meal a day. Of course, this school lunch had to include surplus American wheat bread. A whole generation of Japanese schoolchildren became used to eating bread, and to this day, bread is frequently served with Japanese school lunches.

Despite leaving Nagoya, the industry never stops. On one side a huge Toyota factory, the other, a Honda Industrial Production plant. There are smaller factories everywhere. I look inside one, it’s almost pitch black, with a deafening noise of some machinery, and the heat is unbearable. Who would want to work here? Not many Japanese, that’s for sure. It’s classic DDD work (Dirty, Difficult and Dangerous). As if to emphasise this, when I stop to take a break by sitting on a concrete wall a little farther on, a guy stops his car and asks if I need a lift to the station. He asks me in Japanese, straight out, with none of the hesitancy (will he/won’t he speak Japanese?) that usually accompanies these kinds of encounters. He clearly assumes I’m a foreign worker, a very white Brazilian, although I’m probably pretty red with sunburn by this point.

With factories on either side, the Tokaido is lined with pine trees. It’s like one of those French country roads, but the trees are more twisty, and the fields are grey warehousing. There’s shade, and a pleasant little stream runs on one side. At a Tokaido rest stop a sign warns that trying to sleep here will result in a call to the police. But I’m aiming for a riverside, I know my place.

I’m really flagging, so when I find a park opposite a shrine, I take a long break while trying to fend off mosquitos. The ground is littered with early chestnuts. Eventually, the mosquitos get the better of me, and I’m forced to move on.

The light begins to fail, as once again, the Tokaido merges with Route One. I know the river where I’m planning to stay is not far ahead. I’m worried by the appearance of tower blocks. On satellite images, the river area looks pretty rural, but now I wonder if I’m going to be harassed by local youth. The tower blocks turn out to be beyond the river, in the city of Okazaki. I buy some cider (or cidre, as it’s known in Japan by its French name); I really want something cool, sharp, refreshing, something to take the edge off my sore feet.

I look at the river and assess the best place to sleep. Darkness is falling fast, so there’s not much time to decide. The small grass field opposite the shrine, but close to the road? The “beach” right down in the river? What if the river rises? But the sand is so dry it clearly hasn’t risen for ages. There are no storms over the mountains. I choose the beach.

It’s stiflingly hot. The wind drops until it’s airless. A mosquito somehow gets inside my bivy bag, driving me crazy for a few minutes. A car stops on the road up on the riverbank. A group comes crashing down the riverside and starts to let off fireworks on the next sandbar down from me. When they disappear, no more voices, just the rumble of trains crossing the railway bridge farther down the river and the rippling of water.

One of the things I like about your posts is that you include things that other travel writers seldom touch upon, like the Japanese bakery industry and the history of Pasco. Well, I guess that factories and warehouses are the only attractions when walking that stretch of the Tokaido.