I’ve just finished packing up my bivy bag on the beach, when a large dog comes bounding up to me. In Japan, all dogs have to be on a lead while being walked. I like it this way - I don’t have to worry about being bitten or having a head shoved in my crotch while the owner half-heartedly tries to call it back. The owner turns out to be English. We talk about where we’re from in England. The husband hovers back uncertainly in the distance.

“I’m supposed to keep my dog on a lead at all times.” She rolls her eyes. “But down here, I think it’s safe to let her off the lead for a bit.” I don’t tell her my opinion about dogs on leads, the dog is friendly, and I admit to having spent the night on the beach. No disturbances, just some people letting off fireworks.

She walks on with her dog, and I finish packing up my things. I’ve had about thirty minutes of sleep again. But I’m feeling refreshed after washing my hair and showering with bottled water. Still, I must look in a state - sometime in the night, I pinged my headtorch right back onto the bridge of my nose. It didn’t hurt much, but sent an incredible amount of blood flowing down the front of my face, so much that I couldn’t believe it was blood. With no mirror, I’ve no idea what my face looks like now.

Okazaki Castle in the distance, with the beach where I slept in the foreground!

I’ve not read up about Okazaki before getting here. So the city is a pleasant surprise. Shaded gardens surround the castle area, opposite an area of miso breweries, and a well-tended riverside walk leads up to where the Tokaido continues with a series of turns through the city of Okazaki. There are 27 turns in total, marked by a monument at the beginning and end of the series. Luckily, I have my guidebook now, and I can navigate my way through the 27 turns without too much trouble. The route of the Tokaido through Okazaki was established in the 1600s as the outer castle earthworks and a series of moats were constructed. The route ended up twisting between the earthen ramparts that marked the castle city boundary and the moats that enclosed the castle area.

I would have liked to stay in Okazaki for longer. It was too early for the castle to be open, and a visit to a miso brewery (one of which was established in 1337) would have been nice. But, I need to get moving, and carry on through the eastern suburbs of Okazaki. The sandals that had only chafed the day before, are now suddenly giving me enormous blisters. I stop in a park under a horse chestnut tree (the only one I’ve seen in Japan until now) and assess the damage. There are blisters around the sides of my feet, my heels, and a huge one the size of an umeboshi plum on the ball of one foot. I stick plasters over as many blisters as possible and then change my socks.

I reach the edge of Okazaki at the Oto River. The Tokaido stops, the old bridge has long gone, and I have to loop round and use the Route One bridge to cross the river and pick up the Tokaido on the far side. Where the road meets the river, there’s something strange - four scarecrow-like figures protruding from the crash barrier supports. I think they’re there to help drivers navigate the ninety-degree corner without ploughing into the crash barrier. But their strangeness, and the abandoned houses I find farther up the road make me investigate the area. A track from the corner leads down to a distribution warehouse which houses both a company called Aichi National Electrical Engineering and the Kikumori Youth League - a right-wing group. A cursory look at the Kikumori Youth League website shows a not very youthful group of middle-aged men campaigning for the return of the northern territories (Kuril Islands and south Sakhalin Island) from Russia, dressed in old military uniforms and driving around in military green vehicles crowned with enough sound equipment to wake the dead. The website also sells a selection of goods - calendars, hand fans and face towels (made in Vietnam). The league seems to have emerged from an anti-communist group that formed shortly after the end of World War Two. Strangely, the engineering company doesn’t seem to have any website, this location is supposedly its eastern branch, but there don’t appear to be any other branches and the headquarters has an address listed as an entire residential apartment building in Nagoya.

A few yards further up is a small collection of abandoned buildings. They’re not about to be consumed by a potential landslide like other empty houses I’ve come across along the Tokaido. They’re small, cheaply-constructed, like row-houses from a crowded city centre transposed into a rural setting. Both the roofs and walls are made of corrugated metal sheet. There are still faded curtains in the windows, but the vines creeping across the sliding doors show there’s nobody coming in or out. I can’t find any large factory or anything nearby that would require this group of houses. It’s as I’m passing these dilapidated structures that the umeboshi-sized blister on the ball of my foot explodes, sending a shot of pain through my whole body, followed by the squishy sensation of burst blister and fluid flowing over the sole of my foot.

The mountains start to close in for another pass. The Tokaido, Route One and Expressway One are all about to be funnelled through a gap in the mountains separating the Nagoya basin from the Pacific coast. There are more pine-tree lined sections of the Tokaido. Before the post-World War Two planting of cedar trees for the construction industry, most of the mountainsides too would have been covered with pine. The fast-growing cedars provided faster, cheaper wood and abundant hayfever.

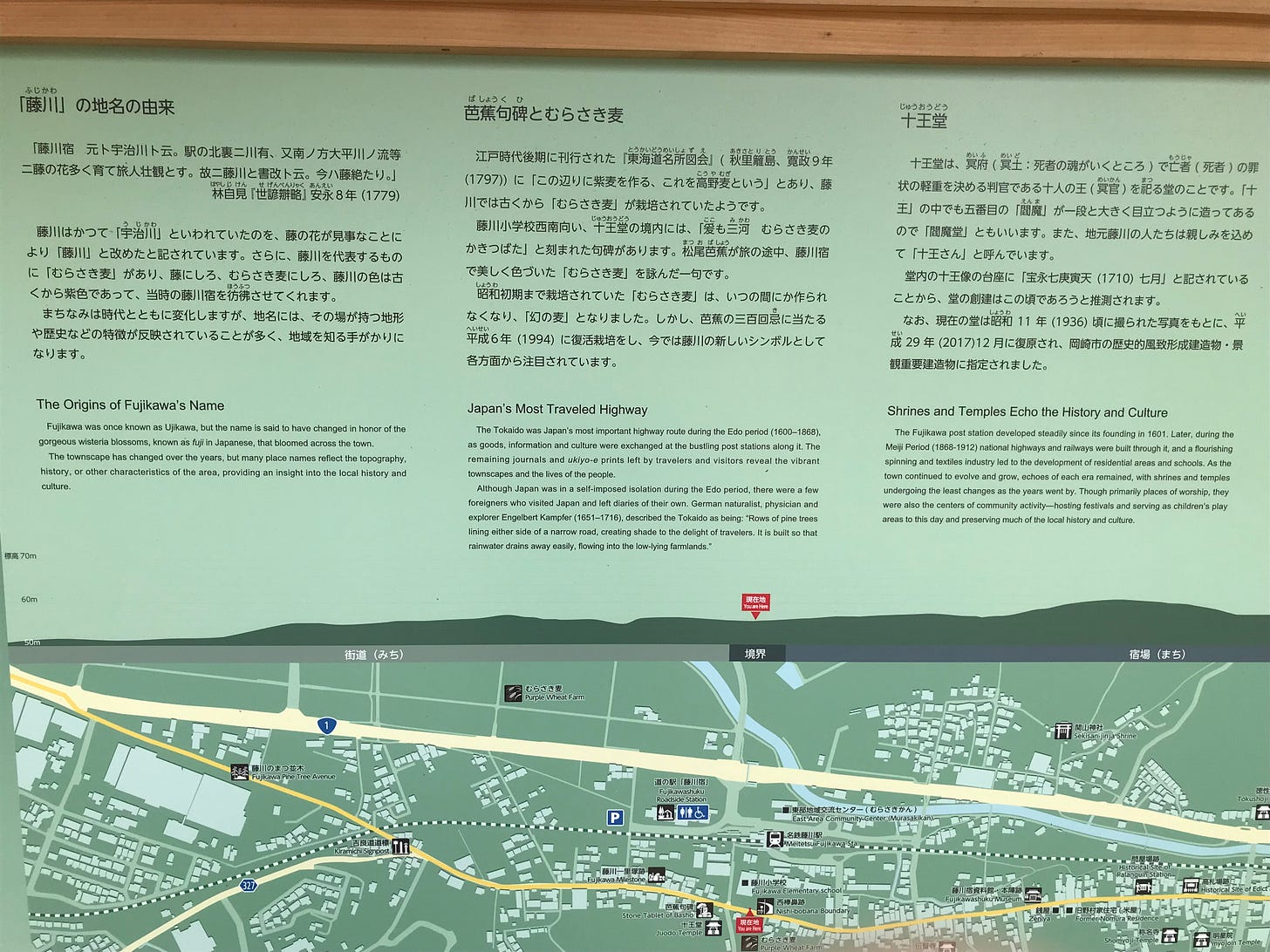

There are auto parts factories near the Tokaido as a reminder of how important the car industry is to this area. In Fujikawa, near one such factory, there are still plenty of old houses along the Tokaido too. Hiroshige has a print of the entrance (my exit from) Fujikawa, showing another daimyo procession leaving town, past the notice boards with local bylaws and requirements for safe conduct passes issued by the bakufu government.

The entrance/exit to Fujikawa, where the kaido (town road) becomes the shukuba (rest stop)

Then, I’m back onto Route One for the climb up the pass. I stock up on food at a Lawson conbini, and down a can of something Hokkaido-inspired that actually tastes pretty good. The little cafe area is roped off due to coronavirus, and the car park outside is too busy to enjoy my lunch here, so it’ll have to wait. When I hit the next town, I trudge around desperately trying to find somewhere shaded to sit and eat my conbini meal. The best place I can find is behind the train station and below the embankment of Expressway One. It’s shaded, nobody passes in the midday heat, but the view of the soundproof fencing for the expressway reminds me of a news story of a homeless man whose body was found between two such fences. I’m slumped against a chain link fence and every so often I discover drains from the station pump out a load of soapy water that trickles across the path, forcing me to move position a few times.

Most of the drop down the far side of the pass is done on Route One, but eventually, the Tokaido breaks off down a small country road, passing through villages of wood fencing and renjimado, separated by rice paddies, following a fast-flowing river. In Akasaka, there’s a museum in an old Tokaido inn. I mask up, hobble in, and try to follow what the old ladies running the museum are telling me. Taking off my sandals and walking up the steep wooden stairs to the upper floor room is agonising. I wonder how the wood in these old buildings is so dark. The old lady explains how the wood beams are smoked to kill any bugs inside and preserve them before being installed.

The Akasaka inn as it would have looked in the mid 1800s. Note the steep attic-style stairs, a killer for blistered feet!

After Akasaka, there’s a nice park, where the Tokaido is once again shaded by lines of pine trees. I stop for a toilet break and am reminded of one of the things I like about Japan - clean toilets. True, there are flies galore trapped in there, but the toilet is graffiti-free and the sinks are spotless. Then, I’m back on Route One for a while before walking along a parallel road through industrial zones and suburban housing.

The sun is beginning to sink as I approach the series of rivers that mark the outskirts of Toyohashi. A wide straight drainage channel shortcuts the looping bends of the Toyokawa River helping speed the mountain waters out to sea and prevent flooding in Toyohashi. I walk along the drainage channel looking for a good spot to bed down. As I walk along the concrete, the reeds rustle at the sides of the channel as hundreds of small river crabs shrink back from my presence. Here and there are dead fish on which the river crabs are snacking. I keep walking until I find a spot which is more overgrown and it’s unlikely I’ll get run over by someone driving along the concrete track. Farther up I can see a parked up minivan, and hear the occupants partying near it. But everything felt safe - until the crabs began to attack.

They scuttled up silently until I noticed one touching my leg. It was too hot to use the bivy bag, so I was lying on my sleeping pad microsleeping, but never falling fully asleep. Were the crabs trying to eat me? Did they think the rippled silver of the sleeping pad was water? After shoving a few crabs away, I got more brutal and smashed a couple to eggshell-pulp on the concrete with my sandals. After that, the attacks stopped.