Coastal Success to Mediocre Suburb

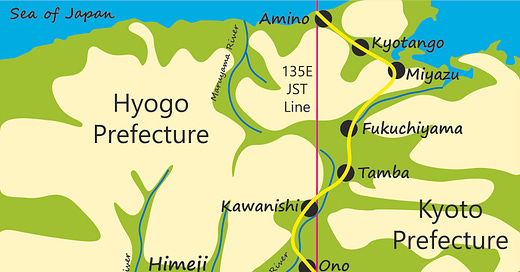

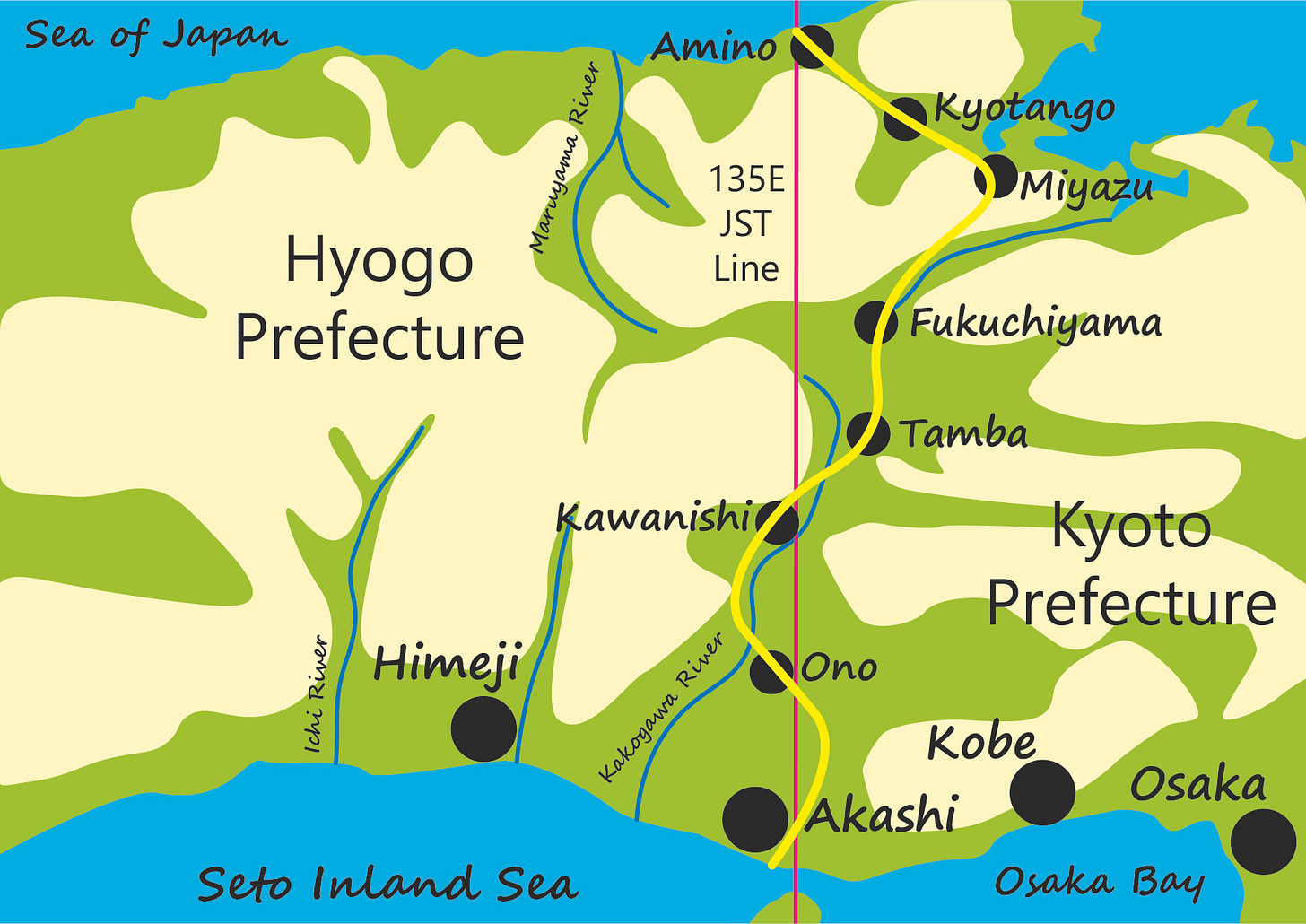

Walking from Akashi City to Midorigaoka along the Japan Standard Time line

Marking the southernmost point of the Japan Standard Time line on the Japanese mainland at Akashi is a simple monument, a ball, face sheared off like a heavily rounded clock, mounted on a cuboid plinth. The flat face of the ball has an image of Japan with the JST line running down it. The cuboid plinth has the single kanji character 刻 (koku/kizamu) indicating a period of time, but conveniently also meaning to carve or engrave.

Behind the monument are palm trees and pines that line this part of the Inland Sea coast. And beyond those are the packed concrete tetrapods where the land meets the sea of the Akashi Straits.

(image from Google Earth)

The first buildings I encounter as I walk away from the coast are two kindergartens. Japan famously has a low birth rate, with many municipalities struggling to keep or attract young families. Akashi city however, is something of an exception to this rule, a success story in its ability to both raise the population and the number of children. How has it done this? Good connections to Osaka and Kobe in one direction, and Himeji in the other certainly help. As do a good collection of big and reasonably successful companies in the vicinity: Kawasaki, Mitsubishi and Kobelco/Kobe Steel. Akashi is a stop on the Special Rapid Service train from Osaka to Himeji, allowing commuters from Akashi to get to Osaka in around 50 minutes.

Location helps, but so does a dynamic mayor. Fusaho Izumi has enacted a series of policies to attract young families to the area. Medical expenses are free up to the age of 18, nursery places for second children are also free and he tripled the number of employees working in the childcare department. (Kyodo News) All this has led to an increase in the birth rate from 1.5 to 1.7, still below replacement rate, but nothing to be sniffed at. The number of children in the city’s schools has grown in almost all areas, and the population has increased steadily for ten years reaching around 300,000 people in 2020.

Unfortunately, this might come to an end. Izumi may have been dynamic, but he was also something of a hothead. Verbal abuse of his employees - in 2019 he told a subordinate to set fire to buildings that were blocking the widening of a major road - was followed by anger management classes, which don’t seem to have paid off too well. In October 2022, he threatened two city assembly members, telling one "I will make sure you lose in the next election". This led to a censure motion, which resulted in the announcement of his resignation, he will probably leave office in April 2023. He’s still very popular with friends I’ve spoken to who live in the Akashi area.

(image from Wikipedia)

As the road begins to rise from the coast, I pass Akashi Municipal Planetarium, the venue of many a school trip. I didn’t go inside this time, but looked at the panels depicting the route of the JST through Japan and did the obligatory standing with one foot on either side of the 135 degrees line. I left through the woodland boundary of a shrine and made my way through one end of Akashi Castle Park. The donjon of the castle has long gone, demolished during the Meiji period to reduce the number of potential regional strongholds. The ruins of its outer walls still remain however, providing a pleasant park with a boating lake, moderately dangerous slides and some tennis courts.

From Akashi, I cut across from one river to another, following the course of first the Akashi river, then the Hasetani river northwards towards my home on the outskirts of Kobe. I soon reach fields, stubbly drained rice paddies and the thick half-tubes of vinyl houses (polytunnels). On the other side of the river are the back end of sprawling suburbs, but this side remains blessedly free of houses. White egrets and grey herons take off and flap lazily upstream before I disturb them again, in a seemingly endless behavioural loop. The valley runs between a chain of new towns - Gakuentoshi, Seishin-Minami and Seishin-Chuo - built in the late 1980s and early 1990s by levelling the tops of the mountains between the valleys. There’s a strange contrast between the modern towns above and the old-style villages down in the valley. You can shift to a different Japan in a matter of minutes.

Then the valley-walking is over. I need to cross back over to the Akashi river valley, but first, I need to walk alongside Route 65, a modern dual carriageway. Luckily, there is a decent footpath, well-separated from the road with its howling trucks. The road goes right through the middle of a golf course. How do they get the balls from one side to the other? Do they chip them over? There are nets covering the road, presumably to prevent golf balls from exploding the windscreens of passing cars. But surely it’s too far? And there are too many trees to aim clearly. I guess, they just carry their balls across the footbridge that crosses the dual carriageway.

Unlike the Tokaido, I don’t have to follow a fixed route. I can choose my own route to minimise the need to walk along big roads. Soon, I cut off the dual carriageway down a minor road through a pleasant village by the Akashi river. I get a can of hot soup from a vending machine, warm my hands for a few minutes until I feel I’ve hit the balance between hand-warming satisfaction and the soup getting too cold to drink. It’s January, and my breath steams in the cold still air, but the sun still feels warm. The valley sides are dry horse-hair-brush brown broken with patches of green bamboo, the valley bottom the dull yellow of rice stubble outlined with white guard rails.

From the Akashi river I need to make yet another valley hop to the Kakogawa valley. This is the last hop I’ll have to make for a while though, as the Kakogawa runs deep into the Hyogo hinterland. A road and railway squeeze through the pass towards the town of Miki on the other side. Then I’m back into suburbs and golf courses around Midorigaoka where I finish today’s walk. Midorigaoka was built in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the peak of Japan’s bubble era, like the new towns on the Kobe subway line we passed before. There is a railway line connecting the suburb to Kobe - it takes about 50 minutes to the centre of the city, a reasonable commute time for Kobe, but too far to be a comfortable commute to Osaka. The elementary schools that are farther from the station have seen steadily declining student numbers for a few years, those that are closer to the station have stable student numbers, but nowhere is increasing like Akashi.

Even if some areas in Japan can be successful like Akashi, it’s a negative sum game. The size of the pie of children is constantly shrinking (an interesting image!) as the national birth rate remains below replacement level. Akashi’s success is likely to be another town’s failure. Places like Midorigaoka with reasonable but not great transport connections are slowly declining overall. How are places deeper in the countryside faring?