Down the Yodogawa

From Yodo to Hirakata City along the Kii-ji route of the Kumano Kodo

The Yodo River’s course has been altered over the years in order to help prevent flooding and reclaim land. Beneath a granite sky I passed across a large open area which, according to a large multi-coloured signboard I took the trouble to stop and examine, had once been marshland and a large lake. Now, it was a wide, rough grassland interlaced with railway viaducts and concrete road bridges. For all the drainage, it wouldn’t have been much more difficult to cross it when it was a bog. I was instructed by a series of signs around pointless loops of track that a cyclist could have completed in seconds, but left a pedestrian like me seething at the lack of linear progress.

Where the Kizu River flowed into the Yodo there was a park. Signs warned of snakes, but I guessed they were still hibernating. I wandered around searching for a bench but had to settle for balancing on the round damp wooden step of a children’s jungle gym. This would be a caravan park in England I decided; here there were only dog-walkers. I ate one of my cheery bulging-cheeked Anpanman buns I had bought in a bakery near Yodo Castle, among the railyards and logistics centres, while my bottom slowly absorbed the damp from the wood. A child approached, wanting to use the climbing frame. I felt stupid — I stood up. It was time to go.

On the other side of the Kizu River, the road was on top of the embankment, and the smooth curve of tarmac this allowed encouraged fast driving. There was no pavement. I watched the jogger ahead of me realise the height of the grass on our side of the road was beginning to push him out into oncoming traffic. The grass was, literally, greener on the other side — the verge there had been trimmed. He twitched to make a break, faltered as a speeding driver shot into view, waited, and darted. He made it. And I scuttled shortly after. But now the traffic was unnervingly behind me and once again I was being pushed back onto the tarmac, this time by a crash barrier. I dropped down a road, white-painted wooden pillars threaded with a single metal pole as you find around streams and ponds in the more picturesque English villages provided the danger-side barrier, and found safety in the squeezed streets below the embankment. Here, the wood frame walls of the houses were covered with rusted grey corrugated iron sheets or Formica-like plastic made to look like wooden panels. From a large election poster for the ‘Happiness Realization Party’ a benevolent female face beamed out. The poster was crisp, new, and the blue and yellow of the logo shone brightly among the drab houses. Tattered pages of pornographic manga fluttered at the foot of the grass bank.

A bunch of school boys waved ‘Harro!’

‘I don’t speak English,’ I told them in Japanese.

‘Good Japanese, good Japanese!’ they said in English as they zigzagged off.

At first, coming from a European country, this assumption that all white people spoke English annoyed me. Why, I thought, did they assume I could speak English, when I could equally well be French, German or even Russian? It’s something to do with being judged solely by your appearance, something all humans do most of the time, but I wasn’t used to it being so in-your-face. Slowly it dawned on me that it was actually a perfectly reasonable assumption to make. Most Caucasian-looking foreigners in Japan are from English-speaking countries. Those that aren’t almost certainly speak some English. The reasonableness of this assumption was brought home to me when a Japanese friend who had lived in London complained that people thought he was Chinese and children said “Nihao” to him. Most East-Asian-looking people in England are of Chinese origin, so it would be a perfectly reasonable (if unsophisticated) assumption to make that he was Chinese.

A nearly-completed mock-Georgian style building was the only sign of economic activity – a photo shop, sign cracked and faded, had turned out to be shuttered. Something made me stop and give the fancy façade another look. I peered through thin wire fencing at the weeds that poked through the gravel, the blue plastic film and stickers still on the windows and the discreet entrance lobby. No construction work had been carried out for months at least. It was clearly intended to be a love hotel (pay by the hour places of ‘rest’), but strangely this one, although clearly new, was sitting in an overgrown building site. The owners must have run out of money before they could open it. Even love had become a victim of recession.

The Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine, often visited by emperors, lay hidden by trees standing over the shabby bank side villages and the river confluence. The shrine was founded in 859CE, to guard the emperor and Kyoto, the spiritual partner to the military Yodo Castle on the other side of the river. As the pilgrimages to Kumano developed, the emperors would certainly have moored their royal barges here and prayed before leaving the relative safety of Kyoto.

After the Kizu, Katsura and Uji rivers merged to form the Yodo, the floodplain broadened out to allow space for a string of golf courses along the river. I left the river to find a train station for my journey back to Osaka, and in doing so, passed through the grounds of a small shrine. A pair of foxes guarded the entrance, their stone heads turned slightly inwards like half-closed pliers. The shrine turned out to be dedicated to the Shinto god Inari. By the beginning of the bakufu period of shogun rule, Inari had become associated with the fox. Gradually the residents of the burgeoning castle towns and trading centres of Japan saw Inari as the fox deity.

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, land reclamation projects like those that had drained the lake and marshland I had crossed earlier in the day, opened up newly-cleared land to arable farming. This land was frequently studded with clusters of trees and riddled with foxes’ dens. Life became harder for the foxes in this new landscape, their old food sources and ability to roam freely had gone. In the towns, the sighting of a fox became a rare thing (you rarely see urban foxes in Japan like you do in the UK). Meanwhile, the economic and social dislocation wrought by the arrival of large numbers of newcomers in these towns led to a desire to rediscover religion, much as with Methodism in rapidly industrialising England.

It was against this background, in the late 1700s, that Inari worship took off. A circuit of Inari shrines emerged in north Osaka, expanding from fifteen to twenty-eight as pilgrimage to the shrines mushroomed. By the 1820s, such was the popularity of Inari worship, the government felt compelled to pass laws regulating folk religions. The fox deity had become dangerous, a popular folk movement in which the leading deity was becoming elevated to monotheistic levels, and a possible focus of popular protest against the regime.

川

I realised on my second day walking beside the Yodo River that I was never going to see any boats on it. In fact the only boats I ever saw were model speedboats whining back and forth as I approached Osaka. When the geisha Ogin came this way, the river would have been packed with merchants and travellers shuttling between the cultural centre of Kyoto and the busy port of Osaka, which in turn connected with other cities across the inland sea.

Heavy overnight rain had left the river slightly swollen with muddied sandbanks on which fishermen twitched their lines into the eddying waters. I ambled happily along in the winter sunshine with the riverbank nearly all to myself. In space-constrained Japan, the river floodplains between the protective embankments are used as public sporting and exercise facilities. I passed through more golf courses and baseball parks filled with children spending their Saturdays doing military-style baseball drilling. Coaches barked orders, children chanted, and mothers huddled and gossiped.

The embankments themselves take a major role in Japanese television dramas. Whenever characters need some space and time to themselves for a really in-depth discussion, it’s almost invariably an embankment where it happens. There aren’t really any secluded lovers’ lanes in Japan, in fact precious few secluded places at all (hence the need for love hotels), so the embankment, or sometimes a rooftop, is the Japanese alternative. It’s as private as it’s going to get here, apart from the fact you’re silhouetted against the skyline for all to see.

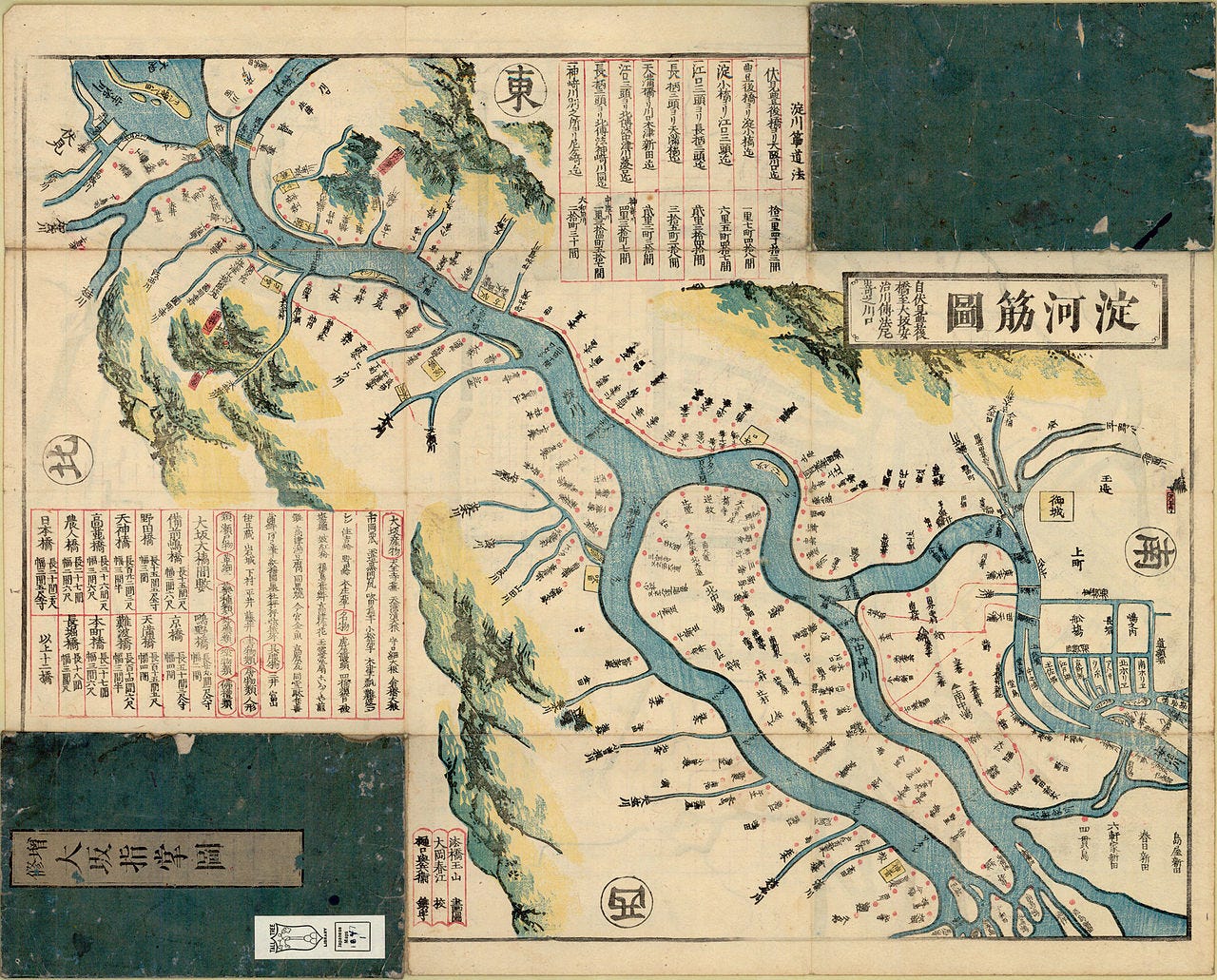

Next to the river I found the Yodogawa River Museum. The museum was open, but I had to be let in by remote control as it was unmanned. I had the eerie feeling of being watched — I knew I was being watched, or else how would they know when to let me out? I had heard the door lock shut behind me. I suppressed the feeling enough to wander round the displays as un-self-consciously as possible. The Yodogawa had once been a thriving trade route. The thirty-koku (one koku being the quantity of rice needed to feed one person for one year) boats that Ogin probably travelled on took passengers and goods down the river to Osaka and beyond. These boats were themselves plied by smaller boats called meshikurawanka ‘Won’t you eat something?’ in the local dialect. The meshikurawanka, with their distinctive call, approached the thirty-koku boats and the passengers would bargain for the sushi, sake and gobo (a type of root vegetable) soup and when the deals had been done the smaller boat would punt off again to find another customer.

By 1912, this leisurely world of small wooden boats was displaced by the arrival of the hikifune — the whistle ships — steamships that splashed up and down the Yodogawa so fast that there was little time to eat. And then in the 1930s the railways came and the whistle ships too disappeared.

A cramped amusement park, its Ferris wheel rising from the trees, appeared ahead. And the riverbank suddenly became a lot more crowded. I had reached Hirakata, a city that was to be the end-point for today’s walk. It was a struggle to find the train station among the urban architecture of a modern Japanese city. Sometimes, when lost, Japanese friends have phoned me asking what I can see in order to help direct me:

‘Well, a lot of featureless block-like buildings which you can see anywhere in Japan,’ I never reply. There are very few obvious waypoints or arresting features in Japanese cities, Identikit concrete with big tacky signs is the dominant theme, which makes finding your way around frustratingly difficult. This is compounded by the lack of use of street names and a Byzantine addressing system. I eventually found my way to the station by climbing up a pedestrian overpass like meerkat popping out of its burrow, sighting the overhead wires of the railway line, and following the line to the station.

An interesting blend of travel writing and cultural history. I really enjoyed this one.

Good point about being spoken to in English.