One week later, on a brighter day, I was back on the Tokaido. It’s late September, it’s still warm and humid, the heat of Japanese summer only fading in the slight chill of early morning. I had actually completed the first part of today’s walk to Seta bridge on that damp first day on the Tokaido, but I felt this part fit better in today’s story.

From the station the Tokaido came close to the shore of Lake Biwa before suddenly turning away south. A security guard eyes me suspiciously from the gatehouse of one of the entrances to the vast Toray Research Center which sprawls over the southern part of Otsu city. Toray is a materials science company that produces a steady stream of innovative solutions for the semiconductor and LED industries and consequently steady stock prices and employment. The Otsu plant started out producing rayon in 1927 by borrowing European engineers and learning from them until they were able to do it by themselves. By the 1950s, they were buying licences from the British Imperial Chemical Industries for the production of polyester and from America’s DuPont, they bought licences for nylon. In the 1960s they were developing their own trademarked products and in 1989 they bought Courtaulds, the company that had first commercially developed rayon fibre. Toray appears to be a Japanese success story. A company that has steadily done the right thing at the right time, expanding in the right way and in the right places. It’s what Japanese companies do well - monozukuri (making things) with incremental improvements. Keep this company in mind, because, as I advance up the Tokaido, I want to compare it both with other successful and not so successful companies.

At the southern end of Lake Biwa lies the Seta River and bridge. It’s the next of the utamakura I will pass on my journey north. In 1223, an anonymous monk, in his travel journal Kaidoki (Journey along the Sea Road) wrote:

If fate decrees,

That I will see again,

She whom I leave with love,

This is the way I will return,

Across the Bridge of Seta.

from: Travels with a Writing Brush, Classical Japanese Travel Writing from the Manyoshu to Basho, Penguin Classics, Meredith McKinney, 2019

The monk was on his way north to Kamakura, a new centre of power formed around military clans that had arisen to the south of modern day Tokyo. He had left his aged mother behind, and the length of journeys of that time left the possibility that this would be the last time he would see her alive.

To the south, the expressway and Shinkansen track cross the Seta River. The Seta bridge itself is broken into two parts by an island. On the island, a sign tells the legend of Seta Bridge:

One day, Fujiwara Hidesato was about to cross the Seta Bridge when he noticed a giant snake blocking his way. But, being a courageous sort of fellow, he hopped nimbly along the snake’s back across the bridge. At that moment, the snake changed into an old man. After a few pleasantries, the old man told Hidesato about a giant centipede that was wrapped seven and a half times around nearby Mount Mikami. Every night the giant centipede would come down from its mountain and eat all the fish in Lake Biwa. The fishermen of the lake were in despair. Everyone around the lake was waiting for a courageous hero to rid them of the centipede. Hidesato at once undertook the great task, to kill the evil centipede. He loosed an arrow that struck the centipede right in the middle of its crimson forehead. The giant centipede was dead! The old man invited Hidesato to live in the Sea God’s palace beneath the Seta Bridge, where he remains to this day, helping to protect Lake Biwa.

The centipedes are the one creature I truly hate in Japan. They’re big, they look vicious, and they can drop on your head without warning. Further on up the Tokaido, I would camp overnight, and I meticulously picked campsites that weren’t likely to be infested with centipedes. They like lots of moist leaf litter, so I deliberately chose ground that was dry and stony, even if it was more uncomfortable.

Beyond the bridge, I pass through endless suburbs, and as the morning wears on, it gradually sinks in that a lot of the Tokaido is going to be like this. It’s monotonous, houses and houses, with little to break the tedium. Much of the Tokaido has nothing to differentiate it from any other road in Japan. Only at particular stretches, where the local government and businesses have decided it’s worth marketing the road, is it noticeably different. These stretches often have a light brown “old road” style coating on the tarmac and are lined with information signs and even rest places for those walking the Tokaido.

Roofs tell you a lot about housing in Japan. Glossy-tiled blue roofs are from the Showa era 1960s to 1980s. Then the fashion switched to Californian-style orange during the late 1980s. Modern houses have flat grey shingle-like roofs. At first, I thought this was a return to a more traditional Japanese style. But you can read too much into these things. More likely, it’s simple economics - tile roofs are expensive to lay, shingle-like asphalt is less labour intensive, and labour costs for construction are expensive in Japan. Perhaps you can read something into the constant post-war desire to emulate western housing styles. There’s a continuous thread of American-style housing, prefabricated clapboard and pillared doorways, running through the whole period. Since the 1990s, there are more Swiss alpine style houses and even more recently a vaguely Scandinavian style has crept in too - the influence of Ikea?

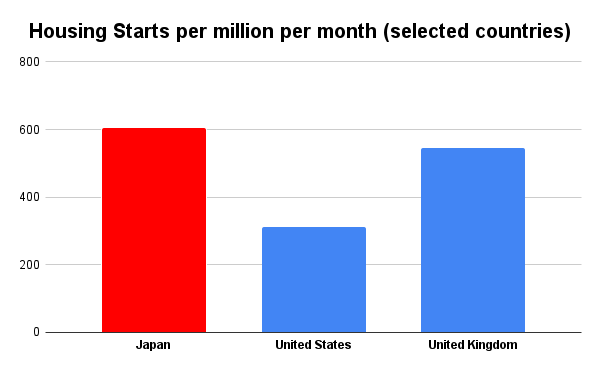

I feel like Japan has got the housing market right, compared to Anglo-Saxon countries at least. Some rough, back of the envelope, calculations show that Japan builds more houses per month, per million population than both the UK and the US. (The UK comes out surprisingly high on this score, I assumed it would have the tightest supply of new homes on the market of the three)

(data sources: tradingeconomics.com, estat.go.jp)

The formation of new households is already pretty much peaking in Japan, and is expected to decline soon, so overall housing supply is much closer to demand. In areas, such as Tokyo, where people really want houses (Tokyo’s population is still growing), housing starts are much higher compared to similar cities such as New York. (Rei Saito at Konichi-Value has an excellent article on this) The result is that house prices as a multiple of income are pretty low in Japan, and the rate of increase in housing prices is much lower than it has been in the US and the UK. Rents have been pretty much flat over the last twenty years too, so housing affordability feels better in Japan. There isn’t the feeling here that you’re chasing an ever-increasing house price that you can never hope to save up for.

But, the picture in Japan isn’t perfect either. House prices have risen slightly, and because wages have barely budged for years, even housing in Japan is slowly becoming less affordable for many. It seems like the wrong kind of houses are being built too. At a corner in the Tokaido yet more suburban housing is being built on fields. In a country with a declining population, and not very self-sufficient in food production, is this really a good idea? It’s family housing, taking the place of fields, but the number of family households is already declining. The remaining increase in household formation mostly comes from single member households, and most of those are for elderly people. Increasing suburban sprawl by building on farmland hardly seems an ideal way to prepare for the future ageing and decline of Japan’s population.

A shrine in a lotus leaf-covered lake breaks the monotony of housing. I sit on a bench on one side of the lake and eat lunch. Behind the lake, I can see yet more suburban housing being built on recently conquered fields.

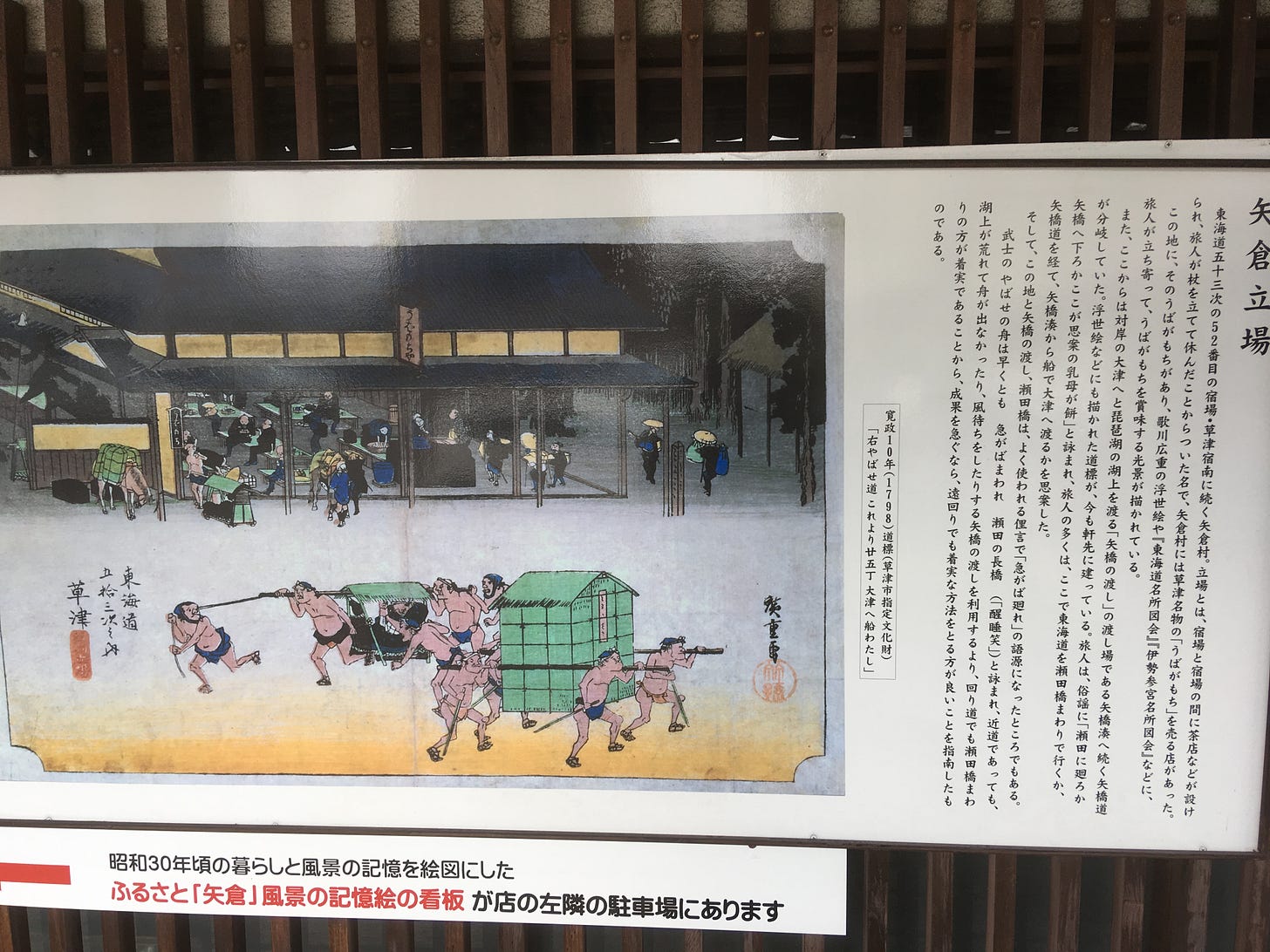

At Yagura bridge, I take another break before entering Kusatsu and watch a late butterfly settle on orange cosmos flowers. Kusatsu-juku is the inn area where Tokaido travellers would break their journey. Hiroshige made a print of a teahouse here. The teahouse serves ubagamochi, a kind of sweet rice cake shaped like a woman’s breast. Why a woman’s breast you ask? Well, there’s a story behind it. Uba can mean old woman, but with a different set of kanji characters, it can also mean a wet nurse. Clearly, there’s a connection between wet nursing and breast shapes, but why would wet nursing be connected with a sweet rice cake? In 1568, Oda Nobunaga was attempting to unify Japan. One of the clans he needed to defeat to do this was the Sasaki clan from Shiga. Nobunaga succeeded in defeating the Sasaki clan on his way to Kyoto, but he really needed to make sure he killed all of the Sasaki clan descendents so the clan could never rise again. However, a great-granddaughter of the Sasaki clan survived and was taken care of by a wet nurse who lived next to the Tokaido. The wet nurse eventually opened a mochi shop to serve travellers on the Tokaido. The shop’s reputation spread, and this style of mochi became Kusatsu’s speciality. I’m not sure why she felt the need to make the mochi into a breast shape though. Maybe she needed to keep advertising her services as a supplementary income?

After dull suburbs, Kusatsu is something of a revelation - there is a street with old buildings, there are model rice bundles outside them. This is what the Tokaido should be like! Kusatsu is where the Tokaido splits. The Tokaido itself breaks off to the east over the mountains to Ise Bay. To the north the Nakasendo route heads through the mountainous interior of Gifu and Nagano prefectures before dropping down into Tokyo from the west through the fashionable resort town of Karuizawa. Kusatsu still has several buildings preserved from the Tokaido's heyday, including a honjin inn where daimyo retinues would stay on their way north and south for their alternate year’s residence in Tokyo. I skip the inn as it looks like it will take too long to look at, and opt for the Kusatsu Juku Kaido Koryukan, a museum that gives a more general overview of life on the Tokaido.

Juku (or shuku) is the traditional term for the old highway rest stops. Kaido are the main roads inside the town, often they are a continuation of the main highways that connect the towns. I felt a little awkward in the museum. I seem to be the only visitor and the receptionist nervously helps me make an ukiyo-e print in the style of Hiroshige as I’m clearly making a pig’s ear of it while trying to follow the Japanese instructions. Upstairs, there are examples of meals that Tokaido travellers in the nineteenth century would eat. There are abacuses for calculating the customer’s tabs, rain coats, hats and the straw sandals seen so often in Hiroshige’s prints. There’s also a room to try on traveller’s clothes from the Edo period, but considering the awkwardness downstairs, and being alone, I decide not to take the opportunity to look like an extra from one of Hiroshige’s prints.

After the museum, I find a long park, raised on an embankment running through the centre of Kusatsu. I assume it’s an old railway line, but it turns out to be an old river, colloquially known as the Tenjougawa (ceiling river). Somehow, as the embankments on either side were built up, the river itself became higher than the surrounding land. The river was actually very shallow, and people could just walk across most of the time. When it became higher, there were porters to carry people and luggage across the river. It cost about 120 yen (one dollar) in today’s money to employ a porter.

The Tokaido runs along the Kusatsu town side of this river park, so presumably only the Nakasendo travellers had to cross the river. The park is so pleasant, I stick to it, rather than walking along the Tokaido below. Children are playing, people are eating ice creams, and I’m walking through them all with a sweaty back and unnecessary hiking boots. And now, it’s back into suburbia.

But slowly, the suburbs peter out. I’m out into open fields for the first time on the Tokaido. Away to my left, a mountain protrudes like a samurai helmet from a flat plain of rice paddy, taro fields and thickets of bamboo. On the right, I see a small graveyard, and the background forest is so dark, it somehow reminds me of My Neighbour Totoro.

I wander down to a solar panel farm that sits on cracked, weed-ridden tarmac and try to take a leak out of sight of the dump trucks that are roaring up and down from an unseen quarry, kicking up clouds of pale grey dust as they go. The road narrows under bridges. Will drivers see me? I squeeze against the concrete sides as much as I can. What if one of those big dump trucks comes this way? But each time, I successfully make it through to the other side.

The road is getting closer and closer to the Yasu river, which cuts this broad valley up to the Suzuka pass over the mountains to the bay of Ise, and to the railway line. Suddenly, from the left, a woman in a headscarf appears, walking more quickly than me. At first, (English teacher bias) I assume she’s an assistant language teacher, teaching English in a local school. But this makes no sense, there’s no school anywhere near here. Much more likely, she’s a foreign student working at a local factory or perhaps a farm. I’m too knackered to catch her up, and anyway, what am I going to do? Run up behind her, tap her on the shoulder and ask her what she’s doing here? We’ve nothing in common except our foreignness.

I make it to Ishibe station. The headscarf woman is there, sitting in the waiting room. But I still can’t think of a way to break the ice, even though it would be interesting to know what she’s doing here. Ishibe station feels like proper inaka - the Japanese word for the countryside. It carries different connotations from the UK. In England at least, nowhere in the countryside is really very far from a significant town or city. In Japan, inaka has a sense of distance and backwardness that’s not just a joke - it really is far to the nearest town, it really is old-fashioned out here.