New Religions and Population Decline

From Funabashi to Tanba City along the Japan Standard Time line

I awoke to dampness. The inside of my bivy bag was covered in condensation, and when I climbed out of that, I found the mountainsides were covered with tendrils of cloud. In the cool of the early morning, on the other side of the valley where the two rivers, Kakogawa and Sasayama, met, I could see what appeared to be a huge temple complex. I had seen this last night, all lit up, when it looked like the bathhouse from the animated film Spirited Away. Despite its temple-like appearance, this enormous building is actually the headquarters of one of Japan’s many new religions - Enno-kyo. Unlike some of the more famous new religions such as Soka-Gakkai, Enno-kyo’s followers only number in the hundreds of thousands, rather than millions. On its website, its doctrine seems innocuous enough - vaguely Buddhist, with a heavy emphasis on ancestor-worship. Like other new religions in Japan, Enno-kyo members place a lot of trust in the founder (or successor to the founder) of the religion, treating them like deities. With new religions, the founder is often a woman, and this is the case with Enno-kyo, founded by Chiyoko Fukada, who lived just up the road in Tanba city at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Enno-kyo Headquarters, photo: Wikimedia Commons

The damp chill was soon burned off by warm sunshine. After pottering about the michi no eki (roadside station) , looking at the information boards and drinking cold canned coffee, I struck out for breakfast, aiming for a Lawson’s convenience store on the other side of the Kakogawa in a sleepy town. From the town I found my way back to the Kakogawa, crossing it and then following the left side northwards. Ducks scuttled away in the river, and in the clumps of bamboo on the other below the riverbank I could see wild boar traps.

Breakfast Stop, Google Earth

I passed an abandoned Chinese noodle restaurant, long-unused fairy lights hanging down in tangled distress. Then old people playing gateball (kind of like croquet) on a little brown sports field. Back again on the riverbank, lines of cherry trees, past their early-spring bloom, the blossoms wrinkled and brown among the grass, but fresh green leaves sprouting from the boughs. Miles and miles of riverbank, but it was pleasant enough, the water sparkled, there were ducks and herons, everything was verdantly green. Last night’s surprise visit by the police had become an amusing anecdote.

I had to leave the Kakogawa behind. It was time to get back to the railway line. So I followed one of the Kakogawa’s tributaries - the Kashiwara towards the town of Iso. The rivers here are still flowing to the Inland Sea; I haven’t crossed the watershed yet where they will flow towards the Sea of Japan. I walked along a country road lined with fields and greenhouses, bundles of rice straw from last year’s harvest drying on racks , but just one road over, parallel to this, I could see the backs of supermarkets, drugstores and convenience stores. Then, suddenly, I was on this strip mall road too and I realise the road is about to plunge into a tunnel. I wait for a gap, then run across four lanes of traffic for the safety of a sidestreet. In minutes, the countryside had gone, I was back in urban Japan. Iso station was set neatly in a new housing estate, but on the other side of the tracks the old kura storehouses attached to the old-style walled-in residences were visible beyond a lumber yard.

Iso Station, Google Earth

Today’s walk was pretty short and uneventful, so I think this is the time to add a little information on what’s happening with the population in this slice of Japan I’m walking through. What I expected before I looked at the data was that as I moved in from the coastal areas and entered the deep countryside, the population decline would steepen, before recovering somewhat as I reached the Sea of Japan coast.

Looking at the graphs below, you can see this is kind of the pattern. Except there is no recovery towards the Sea of Japan coast. I haven’t got that far yet, but clearly it’s a lot more rural than I thought.

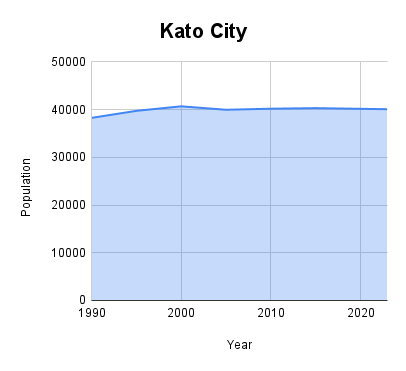

Also, there are some other exceptions. Places like Ono City that are pretty close to the Inland Sea coast seem to have suffered a worse population decline than cities like Kato (near Yashirocho). What’s caused this? It’s hard to know, and needs some research. Ono City seemed to be very bad at retaining the echo boomers (children of the boomer generation, also a great band, if a little repetitive). I’m not sure why. Probably there were few jobs to keep them there, and the coastal cities were close enough to be familiar, and so were easy to move to. Kato City is near the E2A highway and has built a logistics park and has numerous factories and warehouses set up to take advantage of this location.

Fukuchiyama City also seems to have held up quite well. It has a direct train line to Kyoto, which probably helps, as well as being of a big enough size to retain car parts factories and other industry. The key seems to be to provide enough jobs so that young people don’t leave.

The above population profiles for the Japan Sea coast towns show the problem. On the left, the purple bars show the population profile for Miyazu compared to the green bars of the national population profile. The vast majority of twenty year-olds get the hell out of Dodge when they reach that age.

This population profile for Ono City shows a less severe drop off of twenty year-olds leaving the city, but notice the large gap at around 30 years-old (figures are from 2005) compared to the national profile. The echo boomers just didn’t stay. Working in a wire factory (the only significant employer I can see in town) just didn’t seem attractive to them.

Every once in a while, I try to convince my wife to start a new cult - I mean, religion. Lots of tax-free money!

During your walks across Japan, on average, how much ground did you cover per day?