Rainy season is approaching. The ajisai (hydrangeas) have their flower heads, but they are not yet filled with their pastel pink and blue petals. It’s perfect hiking weather — not too hot, not too sunny, an occasional cool breeze. I leave Kamigori, with its overgrown plots of land for sale, quickly behind. Skylarks warble overhead.

I’m following the Chikusa River south, towards the Inland Sea. I’m leaving the Kinki Nature Trail behind, it will soon cross the border into Okayama Prefecture, where it becomes the Chubu Nature Trail. The trail will become too far from the railway lines, too inaccessible, and the steep, sweaty hillsides are not for a sticky Japanese summer. So, onward to the Inland Sea! I will read Donald Richie’s book “The Inland Sea”, and see what’s changed since 1971. Today, the Chikusa River will take me there.

The reeds in the wide river bed sweep downriver, pointing the way. There’s an island in the river bed, and movement catches my eye — reddish brown — deer. One stops and looks, ears at ten-to-two, fully alert. Ten-o’-clock Big Ben school chimes sound across Kamigori and a freight train rumbles over the narrow bridge ahead.

There’s something slightly Indian about the whole scene. The tall, skinny trees with their lush toppings, the wide river. Something that says, “Yes, this is actually Asia, despite the cold winters.”

Sometimes, I can walk along the riverbank, sometimes I am forced onto cracked pavements next to roads. The smut grass bends inwards towards me, like they’re fanning an Egyptian pharaoh, and the knotweed thrusts zigzag-like below. I spot a flock of chickens in a yard and wave at the farmer feeding them, he waves cheerfully back.

I cross a bridge, the water is a deep blue-green, coarsing over rocks and slowing in eddying pools. In one of these pools, two turtles swim lazily like holidaymakers.

Back on the riverbank, I stop for an early lunch. Seven-Eleven has the best sandwiches of any conbini in Japan: bread that actually has texture, not foam-passing-as-bread, fillings that aren’t overly-complicated, two or three main fillings at most, with a decent amount of protein in them.

From a thicket of chinaberry trees, a pheasant calls, it’s time to move on. The valley broadens out, fields of almost-ripe barley and purple-flowered vetch, and in the distance, the raised track of the Sanyo Shinkansen across which the hissing trains slide.

The mountains to my left look like they’re from a late eighteenth-century English landscape painting — rocky hillsides, covered with trees, and faintly billowing clouds behind.

The river wraps around promontaries of mountains. At one such promontary, it starts to rain — big fat drops, but I’ve reached the shelter of the big trees at the bottom of the mountain that overhang the road. I can see it’s just a shower, so I wait it out, like I would in England, peering at the sky among the treetops. “It’s definitely brightening up!” Finally, the rain stops, leaving a damp ground that steams in the early-summer heat.

As I walk through a village, a formation (two pairs) of junior high school kids with their shiny white cycle helmets passes me. One of the first pair says “Hello!” to my head-knod as they pass, but my return “Hello!” ends up aimed at the second pair, who smile coyly.

My aim today, is to reach Ako. It’s a little famous for its connection to the 47 ronin, the masterless samurai who avenged their seppukud lord. Most of the action actually took place in Tokyo, but Asano Naganori, the daimyo lord, had his base in Ako. The remnants of his large castle remain, and there are a couple of museums too.

I think I’m nearly there, but there are miles of suburbs to trudge through first. New-build houses, driving schools, supermarkets surrounded by tarmac fields of car-parking, old people’s homes, ugly hospitals. Finally, I make it to the castle ruins.

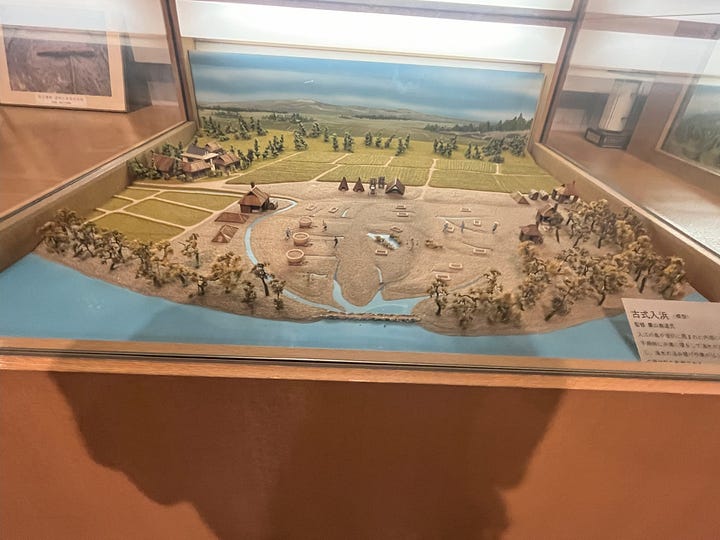

First, I go in the Ako museum of history. On one floor it tells the history of salt production in Ako, which was the city’s main product, exported all over Japan, particularly to Edo (Tokyo). There are models of the salt fields, where the water is evaporated to create brine. This is then tipped into channels and taken to boiling rooms, where it’s further evaporated until only the sea salt remains, to be packeted up and shipped around Japan. The second floor has a little about the 47 ronin, how the story was developed. It also shows how the castle town of Ako looked at the time of the incident.

Then, it’s on to the castle ruins themselves. They’re a disappointment — messy and unkempt. You can see they’re trying to redevelop parts to make it look better, but there are 1970s concrete buildings and tatty sheds among the weed-choked grass. The former location of the castle itself is marked by… concrete. Behind it all, towers the chimney of the local chemical plant. Akashi has castle ruins too, and has made a nice park out of it. Fujiwara-kyo, near Nara, has done a much better job of giving the impression of the scale of the Fujiwara palace, but tastefully, by placing shortened red pillars among the grasslands of the Nara plain.

You can see they’ve tried to make the town look nicer too, but parts of it are late showa-era concrete ugliness. The boom times for the local industries must have ended then, but tourism just hasn’t been able to make up for it.

I think the disappointment is because I had expected a quaint seaside town, not an industrial one. I thought there would be castle ruins by a sparkling blue sea, with the distant shapes of steep-sided islands. I thought I’d left the industry behind in Akashi and Himeji, but maybe this is its last gasp before things turn more picturesque.

Sorry the final destination was a bit disappointing - but thank you so much for the lovely descriptions and revealing Donald Richie to me; can't believe I've never heard of him before!

I hope it was indeed the last gasp!