Today was a short walk, less than 20 kilometres, although finding somewhere to sleep at the end might be a challenge. But first, I had to leave the delights of Fuji City behind. The whole of the eastern part of the city is dominated by the ranked grey serrations of JATCO’s car parts plants, block after block of them.

JATCO is another of Japan’s typical car parts manufacturers, owned by the car manufacturers they make parts for. In this case Nissan, Mitsubishi and Suzuki. It has industry standard operating margins and seems to be doing reasonably well. Not so Nippon Paper, the manufacturer plastered across the centre of Fuji City near the main train station. It has rising debt and negative operating margins. In 2019 it closed down its championship-winning ice hockey club, Nippon Paper Cranes. Earlier in 2023 they closed down the last white paper plant they owned in Australia. They’re trying to branch out into new areas like adult diapers with new paper-like materials and the possibility of growth as the traditional document paper market declines.

Then, I was over the Numa River and out of Fuji City. Well, not quite. Nippon Paper’s Unitech plant kept me company with its steaming pipes, red-and-white-striped chimneys and slanting conveyors protruding over the rooftops for a few kilometres. The sea was somewhere over to my right, but hidden by an embankment and a screen of pines.

I had imagined walking alongside sparkling blue seas, past scenic railroad crossings with trainspotting photographers and hordes of tourists creating muzukashii groans and agonised faces in the waipu (superimposed box showing the reaction of a celebrity) on Japanese TV. I felt like this was the kind of area for that, but maybe I was thinking of Kamakura much closer to Tokyo. Eventually, the embankment disappeared, but the sea was still hidden behind a veil of pines. To relieve the tedium of road-walking, I walked along a parallel path among the pine trees instead. Then I realised the Tokaido had moved farther inland, and I had to short cut back to the dullness of suburban housing. There wasn’t really anywhere to stop along this road; among the pines I had been able to take frequent breaks. The result was I was already in Numazu by just after midday.

The grasslands of Hara 原 in the early morning (indicated by the red colouring at the top of the picture) as depicted by Hiroshige. Mountains in front of Mount Fuji have been removed to give a sense of the size and splendour of Fuji-San

(Wikimedia Commons)

I took my time eating lunch in Doutor cafe. I like Doutor, it has a simple drinks menu without the overcomplicated faff of Starbucks’s seasonal specialities, and it’s cheaper. I watched the other clientele from my corner, the immigrant mother struggling with two children, the cocksure businessman with the big face and pomaded hair with his meek partner, the old man struggling with the shiny menu.

The Kano River in Numazu

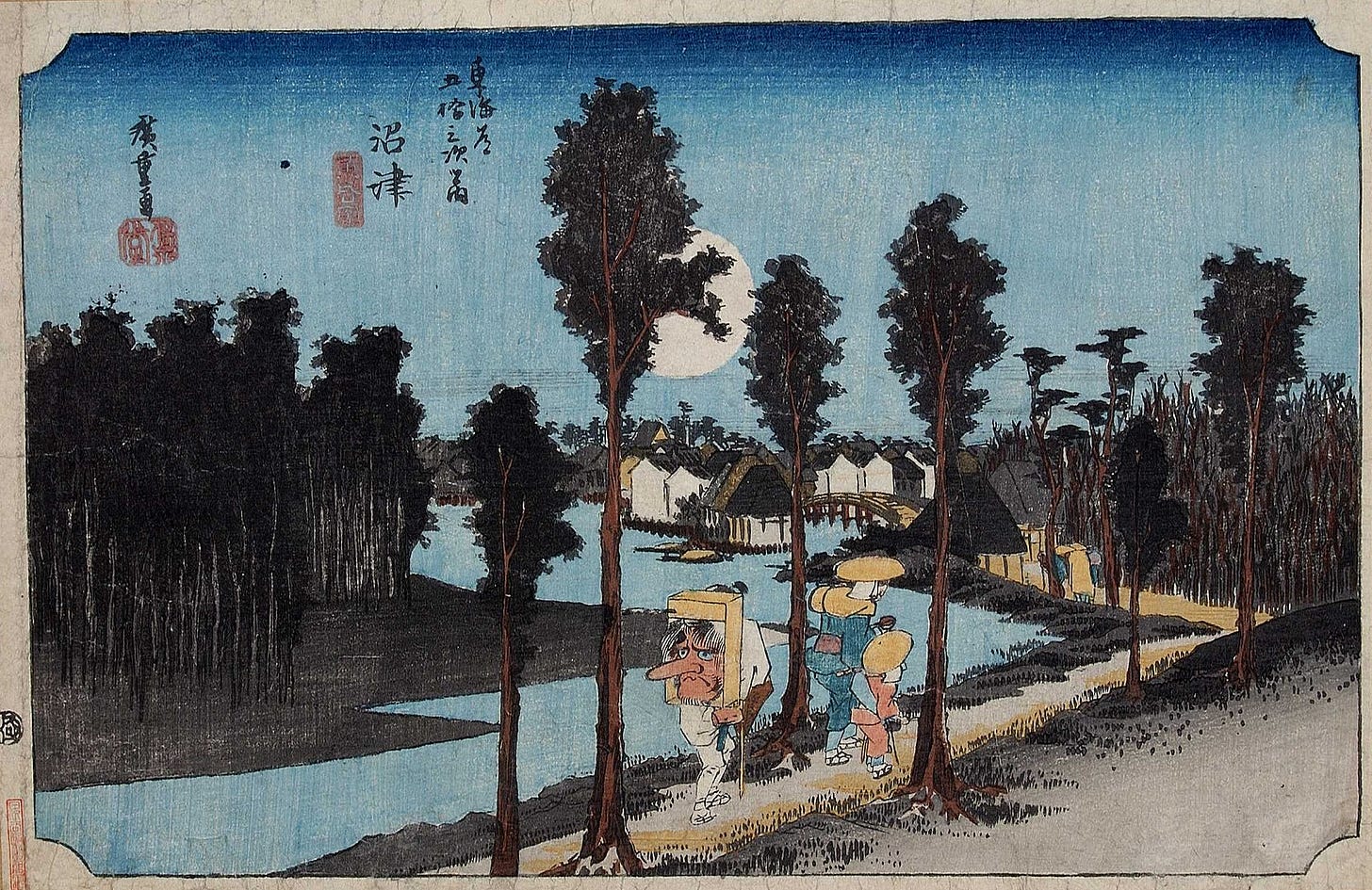

Numazu and the Kano River as depicted by Hiroshige: the pines that currently stretch along the coast from what is now Fuji City surround the town. The white walls of houses in Numazu Shuku are visible, glowing in the light of the full moon in the middle background. One of the travellers just about to reach the safety of Numazu post town is carrying a large tengu mask, perhaps to be used in a festival or Noh drama. (Wikimedia Commons)

I hung around for a while in a park by the Kano River, reading about the castle that had once stood here, of which no trace seemed to be left now, then continued up the Tokaido, following the course of the Kano River. It was too early to think about sleeping now, but I had half an eye open for a good place to camp out.

I left the rivers behind. Until now, I had always slept in a riverside park, and leaving the sleep opportunity of the riversides seemed risky. But I pushed on, past another ichirizuka distance marker. I was looking forward to the section over Hakone tomorrow—mountains, lakes, paths instead of roads.

The suburbs of Numazu blended into those of Mishima, so I was never really sure which city I was in. Then the suburbs petered out into farmland—Mishima was already over. The rivers were too small for riverside parks. The Tokaido climbed a steep slope and deposited me next to Route One—Hello deafness my old friend. This part of Route One was lined with pines in traditional Tokaido style, but only one carriageway benefitted from the shade of the pines, and fortunately for me it was the Tokyo-bound one. A pleasant path ran along the embankment above the road and among the pines, past vegetable plots and another ichirizuka mound.

Silhouettes in the morning mist at Mishima Taisha Shrine next to the Mishima Shuku. (Wikimedia Commons)

I could see on the satellite view on Google Maps that the Tokaido was about to begin its long ascent to Hakone. Small villages, small roads and suspicion would follow once I started that section. I needed dinner and a place to sleep. I had already bought dinner from a Seven Eleven a while back and now a series of loops in the interchange between Route One and Expressway 70 provided a convenient no-man’s-land island where I could rest and possibly get a noisy sleep.

Bamboo screened me on one side, and the long summer grass and fixated stares on the road ahead of passing drivers hid me on the other. The cars were noisy, but strangely comforting, there was enough light to see well enough that nothing was going to surprise me. It felt like one of the safest places I’d camped yet.

Wild.

Wait. Are you sleeping roadside on these travels, like in bamboo and grass?

I’m waiting for you to find breathtaking scenery. It must exist. But when I read here about red chimney stacks and then the phrase “I had expected a shimmering sea,” I thought uh oh. This trip for him is going to be a bust. (It is indeed true though that we have to search out the picturesque spots now in Japan following its seven decades of industrial, who the fuck cares self-pillaging.)

I am partial to Numazu not at all for the looks of the town but for its amazing fish markets. At least there is one reason to stop there.