Travellers on the Tokaido in the Edo period usually walked about forty kilometres (twenty-five miles) a day. Until now, I had only walked about twenty kilometres a day along the Tokaido, but today would be different. Railway lines had run parallel to my walking route all the way from Kyoto; as I crossed the Suzuka Pass, the railway would follow a different route farther to the south, with only the Route One highway and the Tokaido going over the pass. Today’s walk could be as long as fifty kilometres.

From Ishibe station, I set off between old houses clad with vertical dark-wood strips, while a procession of uniformed junior high school students pass on their way to school clubs. I know this is inaka because the students are all wearing their white, perfectly round, bowl-like cycling helmets. City kids wouldn’t be seen dead wearing these. Only super-serious racing cyclists, inaka junior high school kids and Mormons (always in pairs) wear cycling helmets in Japan.

Here and there, the line of old houses breaks for a bridge over a small river flowing down from the mountains close to the south. There are flower beds outside some houses with utsukushii Tokaido (beautiful Tokaido) on them. It’s pleasant walking, quiet streets, not the howling swoosh of Route One which I’ll meet later. Now there are short stone tunnels which pass under…something. I climb up the embankment of one to investigate. There’s nothing there. Was it an old railway line? Later, next to one of these short tunnels I find an information sign. They were to carry water over the road, these are ceiling rivers like the one in Kusatsu. As the surrounding land was levelled and worked to create new fields, the river effectively rose in height compared to the landscape. Now, the river has been redirected again (with the help of concrete, naturally) and runs back under the road.

There are public toilets accessible from the outside of a community centre. Imagine finding this in England. They’re sparkling clean. I can’t quite believe I’m allowed to use them, so I sneak in and out as quietly as possible.

“Proibido Jogar Lixo”, a sign says in large red letters behind an apartment building - “No Littering” in Portuguese. It’s the first indication of one of Japan’s largest immigrant groups, the Nikkeijin from Brazil. I’m entering Japan’s immigration belt, a collection of prefectures with the highest numbers of Brazilian immigrants. Shiga prefecture, which I’m currently walking through, has the fifth highest number of Brazilians, neighbouring Mie prefecture, over the Suzuka pass, has the third highest, then the next two prefectures I will walk through - Aichi and Shizuoka have the second highest and highest numbers respectively.

In 1990, the Japanese government revised the immigration law and began to allow large numbers of Nikkeijin (descendants of Japanese emigrants in South America) to immigrate to Japan on Long Term Resident visas. They mostly came to work in the manufacturing industries which were located across the central region of Japan from Nagoya on the Pacific coast, to Fukui prefecture on the Sea of Japan coast. The number of Brazilians in Japan peaked at around 314 thousand in 2007, before declining to around 173 thousand in 2015. After that, the number recovers slightly. The decline was the consequence of deteriorating economic conditions after the Lehman shock. The Japanese government even gave payments between April 2009 and March 2010 for those on Long Term Resident visas to leave Japan and stay away for three years. The slight recovery in numbers of Nikkeijin and desperate advertisements offering free flights, apartments and large sign up bonuses during the Covid pandemic point to the tightness of the labour market in these manufacturing areas in recent years.

The houses fade away to clumps of bamboo, the Yasu river is close, but unseen on my left, and on my immediate right, the single-track railway, which fortune-permitting, will take me home tonight. The road runs right through the middle of a recycling plant - on one side the main shed, the other, piles of crates and enormous bags of unprocessed plastic. Then the road climbs, stonewall-lined either side, through forest. It’s like a sunken Derbyshire lane, except the stone is piled diagonally to make a diamond pattern. I emerge in a vaguely Alpine setting with houses across the railway track set in climbing terraces of naturally short grass and surrounded by pine.

As interesting as the road was, I didn’t realise it wasn’t the Tokaido. I hadn’t bothered to invest in any books about the Tokaido at this point, all my information was gleaned from websites. Someone had made a nice GPS cycling route of the Tokaido, coordinated with an online mapping service. So far, I had used printouts of this, combined with squinting at my phone to check my location against the map. This phone-checking ran my phone battery down pretty smartish, so I used it sparingly. Somewhere farther back, I should have crossed the Yasu river and followed the Tokaido straight as a bamboo rod across the river plain to the town of Minakuchi. Instead, I was bearing away far to the south, following a southern tributary of the Yasu river, the Soma river, and adding a few more kilometres to my journey.

But, hey-ho, the road had little traffic, and the scenery was nice. It was easy to break off the road for a call of nature in one of the many bamboo thickets along the river. Swelling jellyfish-like clouds dragged their rain tendrils across the mountain range and plain to the west, but they didn’t threaten me yet. I took a break on Dairy Milk chocolate bar-shaped concrete by a bridge over the Soma river, then crossed the bridge to head into Minakuchi the long way round.

By the time I reached the centre of Minakuchi, those threatening clouds had finally reached me. The tendrils, curving gracefully at a distance, started to drop like falling acorns on the narrow pavement. Behind me, two foreigners (Brazilians?) struggled to get past on their bikes. I really needed to sit down and rest properly. So I went into a large Seiyu shopping centre to escape the rain. The Covid pandemic was now in full swing, and fear made everyone on edge. I’d been masked up all day, I had crossed a prefectural boundary (not recommended), but I reasoned that I would be very socially distanced. A McDonald’s meal in a shopping centre wasn’t ideal, but my table was far away from others, and the number of infections at this point was very low.

Hiroshige’s woodblock print of Minakuchi shows a line of thatched houses, in front of which, a group of women are busy stringing up the flesh of bottle gourd - kanpyo. This was Minakuchi’s speciality back in the Edo period, and is still quite popular today, being used as an edible string for cabbage rolls and kinchaku tofu parcels.

After some trouble, I rediscover the Tokaido route and leave Minakuchi behind with no time to investigate its castle. I really must push on. The mountains and Route One close in from the north. Tiny fields of tea begin to appear. Bushy rows which appear uneconomically small. I’ve always wondered, as I’ve passed on the Shinkansen to Tokyo, what the electric fan-like objects are which surround some of the larger tea fields. It turns out that the fans are there to warm up the tea bushes. They help prevent frost damage to the new tea shoots (shincha, the most expensive tea) in early spring, by propelling warmer air downwards when the ground temperature is below the air temperature. It’s difficult to imagine that those small fans can do much, but somehow, they work.

I find a Tokaido rest shelter, the inner wall covered with post-it notes from walkers. I haven’t seen a single other Tokaido walker today. The newer post-it notes are mostly wishes that the pandemic will soon be over. Eradication seems vaguely possible in Japan at this point as they are managing to keep their R rate (remember when we didn’t know what this meant?) below one.

I finally get caught full thwack by the rain as Route One closes in a pincer movement with the Yasu river. There’s no escape this time. An umbrella keeps the worst off while the smell of damp earth mixes with traffic fumes. It’s mid afternoon and I still have to cross the Suzuka pass, it’s likely to be dark by the time I’m finishing my walk. A quick cut across to a Lawson convenience store and back equips me with a sleek white torch (not great for hiking, but it’ll do) and a battery pack for my phone as well as a whole pack of batteries.

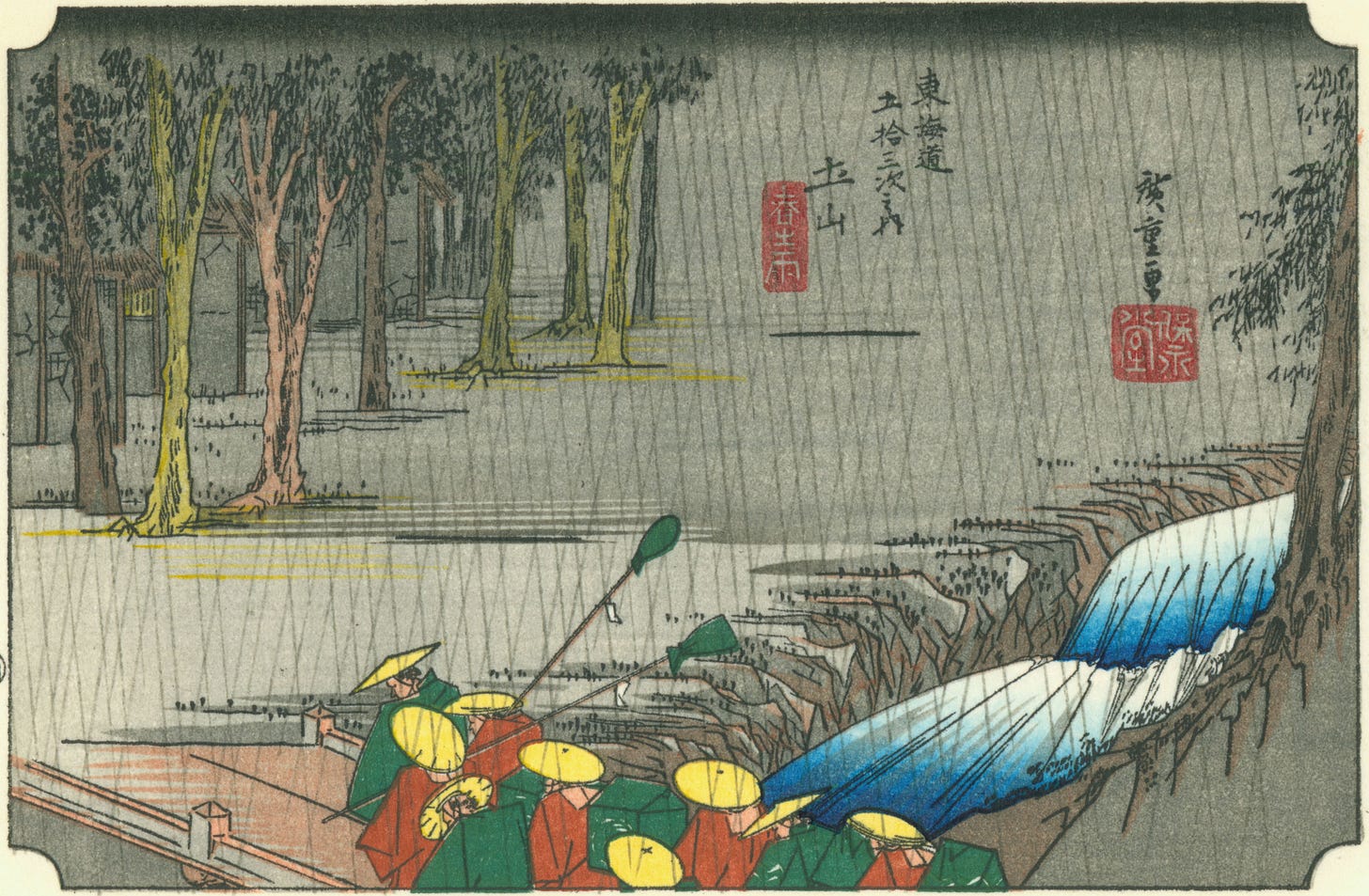

I plug on, the tea fields become more frequent and the mountains of the Suzuka pass begin to loom ahead. I cross a pedestrian bridge over a river like one extended bus shelter into Tsuchiyama post town. Hiroshige has a print of a daimyo procession crossing a bridge at Tsuchiyama. The bus shelter covering would have been ideal for them as Hiroshige has the procession hunched over in the rain under their straw hats. The rain in his picture comes down in great slanting lines as they progress towards the cedars of Tamura shrine.

The cedars and the shrine are still here, but the rain seems to have ceased for me today. After a sharp right turn in the cedars I end up passing through the middle of a large modern factory. The Tokaido really does go through the middle of this factory too. I had to check I wasn’t going the wrong way and actually entering the factory. As it’s been so obtrusively slapped across the Tokaido, I think it’s only fair to find out what this factory is.

G-Tekt is a parts supplier to the car industry. About half the parts it makes are supplied to Honda, but it provides parts for a variety of other car makers too - from Jaguar Land Rover to BMW. Like Toray in Otsu, G-Tekt has stable profits and employment and has gradually expanded overseas. It started out as a simple metal pressing company before moving up the technology ladder to the latest vehicle transmission systems. Again, it’s what Japanese companies do well - monozukuri with gradual improvements.

The Tokaido and Route One merge just before the Suzuka pass. I’ve been worrying about this all day. How do I get across the pass? Do I have to walk through the tunnel along Route One? More worrying, it’s already starting to get noticeably darker. At least there’s no more sign of rain. And why do all the fields here have huge electrified fences surrounding them like something out of Jurassic Park? Deer? Wild boar? Bears?

A decaying restaurant alongside Route One does nothing to put my mind at ease. It’s the kind of place that’s reputed to be haunted and visited by YouTube vloggers. A service road climbs the mountainside on the left and affords me a view of the tunnel entrance. There’s no pavement and clearly no way I can go through the tunnel. But I can see a road that breaks off to the right and goes over the top of the pass. How to get there? I go back to an underpass I missed before and start up the right side of Route One. There’s a signpost on the road with a picture of two old travellers on it. I’m on a proper route over the pass! There’s even a collection of bamboo sticks, one of which I happily take, to fend off bear or boar as necessary.

At first, it’s a steep but easy track to the top of the pass, where there are yet more tea fields. A sign advertises a diversion to some tourist attraction. But no, I need to push on down, into forest, skipping around shark-fin rocks before the light fails completely. The path drops to where Route One has reemerged from its tunnel. It’s almost dark, but not quite. There’s a path marked as the Tokaido which continues downwards into deep forest. But it’s inky black in there. I prefer the relative safety of walking along Route One, the pavement is wide, even if the cars swish past pretty close and surely no wild animals will be so close to the road.

The pass is not too high or demanding for those without baggage, even during the Edo period. But for those back-burdened with the kind of enormous loads shown in Hiroshige’s prints, the Suzuka pass was still a tough proposition. To help carry larger loads, packhorses were employed. A mago horse-driver would lend a packhorse to those needing it and guide it over the pass. The mago would sing a song to help keep the rhythm along the steep path. A typical song had lines of five or seven syllables, like this one:

The slope shines,

The Suzuka mountains are cloudy,

Rain falls,

on Ai no Tsuchiyama.

坂は照る照る

鈴鹿は曇る

あいの土山

雨が降る

Saka wa teru teru,

Suzuka wa kumoru,

Ai no Tsuchiyama,

Ame ga furu.The adrenaline rush of crossing the pass gone, I notice how tired my legs are. The hiking boots swing like pendulums at the ends of my legs, the entirety of which, from thigh to ankle, ache with a previously unknown intensity. Route One has markers every one hundred metres, which at first seem to mark progress, but then seem to mock me for a lack of it. I pass a barbecue restaurant, lights on, I can see benches, chairs and people sitting on them chatting and eating. Further on, in a quiet village, I scrutinise the bus timetable in a pool of streetlight. There are no buses. Now I worry, is Seki station actually a train station? Or is it a michi no eki wayside station selling regional specialities? Because there are signs for this wayside station all along this stretch of Route One. I check my battery pack-charged phone. There really does seem to be a train station in Seki. I check the train times, are they running this late? It’s still early evening, but in the darkness it feels much later.

As I reach the outskirts of Seki, I begin to believe I can make it. But the suburbs of Seki drag on forever. The michi no eki wayside station turns out to be a collection of traditional-looking shops surrounding a car park right next to the train station. After limping over the station footbridge, I can finally sit down and wait for the one-man train to take me home.