The Belly Button of Japan

From Nishiwaki City to Funamachi along the JST Meridian Line

I returned to Nishiwaki in Golden Week, a cluster of national holidays at the beginning of May, when the temperatures are like an English summer and the dull, dry brown of winter has transformed into the startling greens of late spring. After weaving my way through a housing estate from the station, I crossed a bridge over the Kakogawa. A group of Chinese? Vietnamese? I wasn’t sure, passed me on bicycles, hollering and laughing, fishing rods trailing from their bicycle baskets.

On the far side of the river, road and railway ran, under cascading creeper and vine, beneath a steep mountain edge. Then I was back on the river embankment, lumber yards on one side and the gently rippling river on the other. The serried ranks of concrete “mansions” I passed next have been taken over by Village House, a real estate company that seems to specialise in buying former local government-owned apartments and renting them out to foreign workers, mostly in rural areas. Their website is nicely translated into English, Vietnamese, Portuguese and Chinese. I’ll see these Village House apartments in nearly every town I pass as I continue up the Kakogawa valley.

In the paddy fields, the new rice shoots are prickling through the smooth water surface. Right next to the paddy fields, a Nissin yoghurt drink factory - a competitor to Yakult. And next to that, an enormous thicket of bamboo, hiding a group of greenhouses that contain rows of some unidentifiable tall plants. And then, an akiya apartment building, one apartment still apparently occupied, but two long since empty, a yew tree with associated climbers hugs the face of the two empty apartments, while a long strand of vine loops onto a balcony trying to find a way through the concrete.

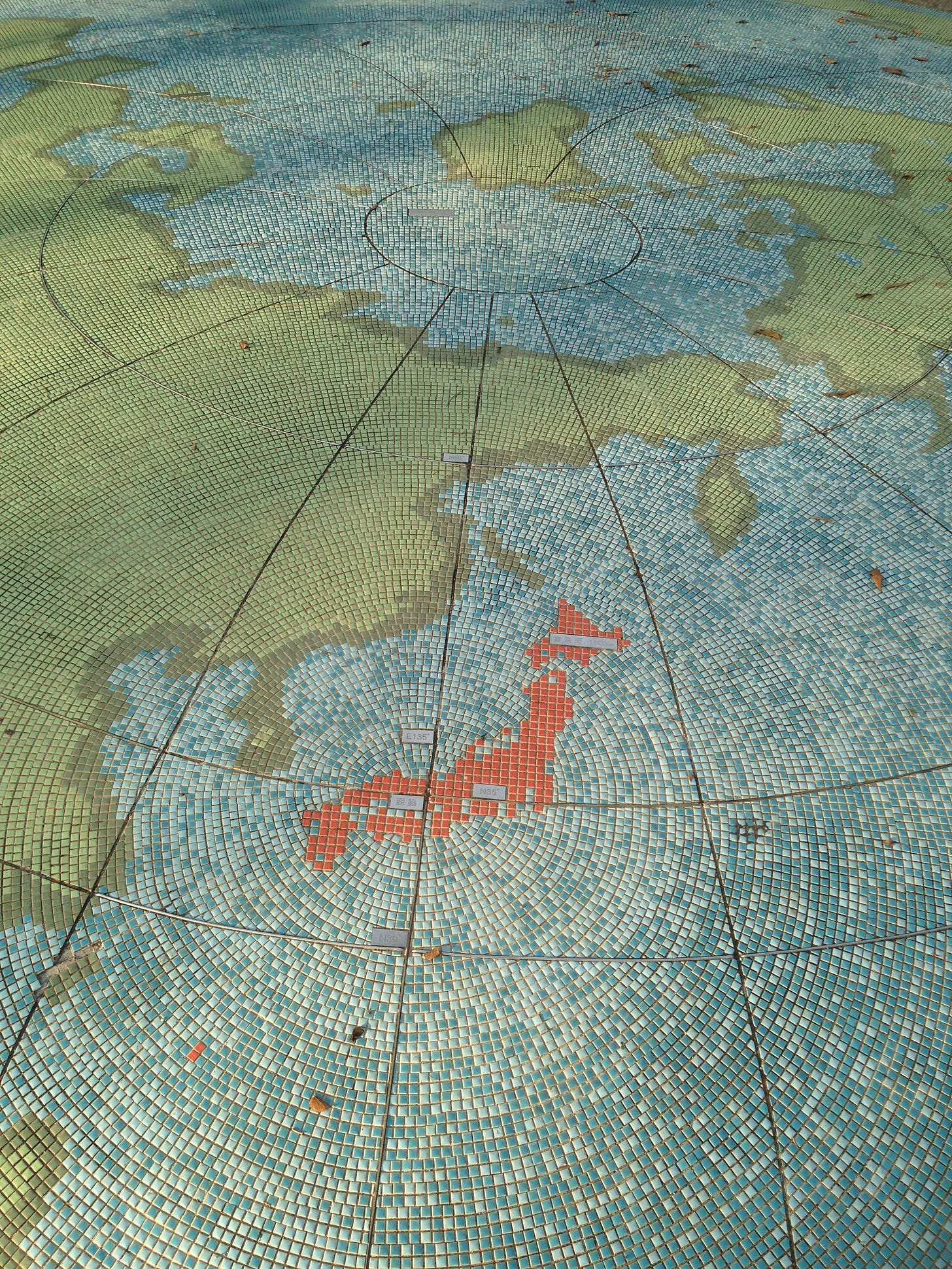

Okanoyama Tumulus marks the belly button of Japan. Yes, Japan has a belly button. This is the point where the 135 longitude line and the 35 degree latitude line meet. The 135 line neatly cuts Japan in half vertically, while the 35 degree latitude line roughly cuts the Japanese archipelago in two horizontally. So, the point where the two intersect is the belly button of Japan. The navel is where life begins, so the belly button is much more considered the centre of the body than the heart. The West Midlands in England may advertise itself as the Heart of England, but nowhere is advertising itself as the belly button of England.

The tumulus itself is one of many across Japan called kofun, often a keyhole-shaped mound, perhaps surrounded by a moat and sometimes decorated with haniwa pottery figures around its edge. These tumuli were mostly built during the fourth century CE, after rice farming had developed allowing a larger population to be supported, but before the arrival of Buddhism. They can perhaps be seen in a similar way to Stonehenge or the pyramids, as the beginning of a time when large numbers of people could be directed to work on enormous public works projects with religious connections.

The Nihon no Heso (Japanese belly button) park, I had visited before, and I skirted my way around the edge of it. There is space here to build bigger. Old buildings spread out, with walled gardens and kura thick-walled storehouses. I passed under a big concrete torii gate, the gateway to a shrine farther up the road. The nursery school beyond the gate looks like something from the Australian outback. A parched sandy-brown play area, broken by dead grass and a single-storey tin-roofed school building. Skippy the Bush Kangaroo wouldn’t have looked out of place here. The shrine buildings next door are definitely Japanese, although there’s something of the Indonesian Batak boat-roofed house about the main shrine building.

I needed lunch, and dinner too for that matter. Convenience stores were few and far between out here, requiring large detours, so when a Yamazaki store appeared on the map near the shrine, I set off straight for it. This wasn’t a typical Japanese convenience store, rather than the clean bright white and robotically polite staff, this shop was dark and dingy with a curmudgeonly owner. I cleared his shelves of anything satisfyingly bread-looking and he scanned through my order without any pleasantries.

I felt watched now. I was quite sure a network of spies were commenting and relaying the message about the strange foreigner walking through their villages. What was he doing? Why was he walking this way? Why was there a sleeping roll strapped to the bottom of his rucksack?

Out of town, past the Belly Button English Conversation School. Then back down to the riverside. A snake basking on the warm tarmac slid off as I approached. The familiar stink of cow-muck from the English countryside, but here it was from three large cow-sheds with classical music playing.

The sun was sinking. There were animal tracks across the fresh black tarmac. Deer clearly, possibly foxes or dogs, but nothing that looked like wild boar. It was a relief, because soon I would be sleeping somewhere near here. Nothing looked too promising until I came to the village of Funamachi. By the river a campervan was parked with a mini-barbecue. If they tolerated campervans and barbecues, they would probably tolerate a little unofficial camping too. So, I stopped, laid out my sleeping pad and ate bread product dinner. As it darkened I set up the bivy bag and sleeping bag. The campervan disappeared, replaced by somebody doing a bit of night fishing. Then he too disappeared.

Just before it was totally dark, there was a rustling in the bamboo thicket next to me. A head poked up, ears pointed. In the gloom, it looked like a small dog, but I knew it was a fox. It froze, smelling the unexpected obstacle of a human in a sleeping bag. Then it retreated.

Strange noises made me switch my head torch on and off. Rustlings, sudden beatings of wings and splashes on the river. Then car headlights. They swung round and came straight towards me. Shit, what if they didn’t see me and ran me over? I stood up. But they stopped and I saw the red light strip on the top. Police!

I knew it was going to go well when I heard the officer at the other end of the radio laugh at the police officer’s report that he had found a British foreigner by the river trying to camp there.

“Aren’t you scared?” the officer asked.

“A little, what kind of animals are there around here?”

“Well, deer and that kind of thing, maybe wild boar, but no bears in this area.”

In truth, it was pretty scary outdoors, in the dark, in a strange place. But that was part of the point - to confront my fears. It’s not a very Japanese response, avoidance of fears is more the order of the day here.

I insisted I was fine here by the river, but it wasn’t whether I was fine that was the problem, the neighbours were worried. They had spotted my flashing head torch light (it only cost one hundred yen and I had to cycle through the flashing mode to turn it off) and were worried enough to call the police to investigate.

So, I dumped my bivy bag and rucksack on the plastic covered seats of the police car and the police officers kindly transported me up to the nearest michi no eki (roadside rest stop) a few hundred meters away where the Kakogawa meets the Sasayama River. I wasn’t sure this was actually any safer. If ever there was a place that was going to attract bears, this was surely it - a nice food source and the forest directly opposite, with no barrier of fields or housing. I squished my bivy bag between a bench and a flower bed and tried to get some sleep. The michi no eki was brightly lit, the light penetrated my bivy and attracted huge moths that fluttered against the outside of it. Every so often a car would draw up, there would be a clank as something dropped from a vending machine and then off the car would go again. On the far side where the rivers met, I could see a huge brightly lit temple complex. Then, I hunkered down in my sleeping bag and waited for dawn.