My parents-in-law’s house lies between a frog-hopping gully and the Hisatsu Orange Railway Line, most of the way up the Tsunagi river valley in deepest rural Kumamoto.

“Oh, Kumamoto!” people will say, “Will you visit the castle?”

I have to explain that actually, we’re at the other end of Kumamoto from the city and the castle, near to Kagoshima.

“What’s the nearest town?”

“Minamata, you know, like Minamata disease.”

“Oh, Minamata,” they nod, and the conversation ends.

The first time I came here, I found a little loop walk I could do, that could also include a detour to the local highlight — the vending machines. Starting from the house, turn left, up the road, past my father-in-law’s vegetable plots (figs, aubergines, peppers), overhung by some kind of orchard, and under the Hisatsu Orange Railway. This railway line runs from Yatsushiro in the north, in mid-Kumamoto, via a scenic coastal route, to Sendai (no, not that one!) in the south, in Kagoshima. Now, the Kyushu Shinkansen hisses through, calling at Yatshushiro and Sendai in mere minutes, but if you want a slow, scenic route, then you can’t beat the Hisatsu Orange Railway.

Anyway, we pass under the water-streaked concrete of the railway bridge, and we’re climbing, an embankment of bamboo grass on the right, persimmon tree and it’s-OK-because-it’s-the-countryside clutter on the left. Still climbing, past 1960s housing with a mini-tractor and attached rotavator, the orange soil of the embankment on the right is studded with pale stones and held together with tree-stumps and their long-dead roots.

The road forks, we take the right branch. Still slowly climbing, past a fish pond with anti-heron netting, the right bank is smoother and shallower, covered with the purple gramaphone horns of morning glory. Now, the left side becomes a bank, terraced with lines of orange trees. But we’re turning right, down a track, the road disappears round a bend into dark forest. Our track drops, between the edge of the forest and a row of polytunnels. What’s inside? We can’t see. We turn sharp right, keeping on the gravel, the non-gravel branch curves up the hill to an unseen shrine in the forest. From every side, the frogs croak and the crickets chirp.

And we’re out, the confines of the embankments and forest are left behind, for flat fields and stunning views across the Tsunagi valley.

Our stride lengthens, feet swinging down the straight road between the electric wires of electric fences and towards the electric wires of the Hisatsu Orange Railway. We peer into the rice looking for the noisy frogs. One rice fields looks different — clearly marked out with a neat lattice bamboo fence and even a little tori gate.

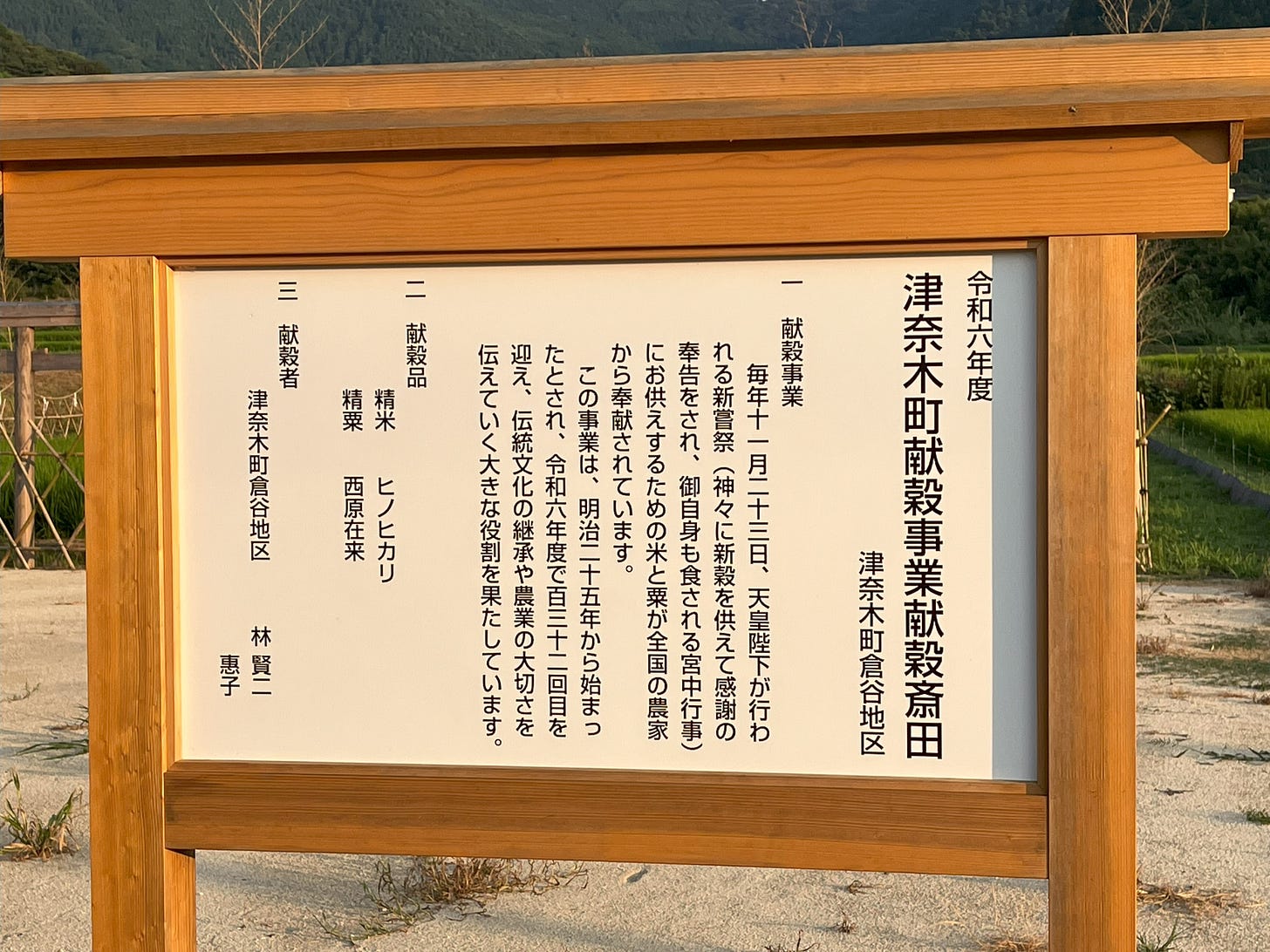

What’s so special about this rice? Luckily, there’s a helpful sign to explain:

Every year, on November 23rd (Labour Thanksgiving Day in Japan), a “new rice” ceremony is held by the Emperor, where thanks is given for the new grain. Rice and chestnuts are gathered from across Japan for this ceremony, which has been held since 1892, during the Meiji Era. This year will be the 132nd ceremony.

We cross back over the Hisatsu Orange Railway on a level footpath crossing, and just after we finish crossing the “bing, bing, bing” and the bee-striped crossing barriers come down. The “one-man car” trundles past, not fully orange like the old Osaka Loop Line trains as I had expected, but just a rippling orange stripe, interlaced with the colours of the mountains and the sea on a white background.

Back along the roadside, next to the railway line. What are those small trees in the field on the left? They don’t look quite right for figs. The Picture This app on my phone has the answer — papaya. They curve out of the straw-covered ground at strange angles, before growing straight up.

Except for these exotic crops, were there any other regional differences. The houses? They looked the same. Were the roof tiles a shade darker? No, they always seem to be a bit darker in the deep countryside. The vegetation seemed a bit thicker on the mountainsides. Many more windows had the tape asterisks to prevent them shattering into a million shards that remind me of Blitz-era Britain. I couldn’t understand these at first, the area isn’t any more prone to earthquakes than anywhere else. What it is more prone to, I realised a couple of days ago, is typhoons.

The road drops, slowly down, the white one-storey house, we’d call it a bungalow in England, reappears. I rub my fingertips on the mint growing by the never-locked front door and we re-enter to the smell of old cooking oil, incense and tatami that pervades these old Japanese houses.

Some bonus photos of the Tsunagi area not on the walk:

As a massive fan of Hayao Miyazaki, you could not keep me out of exploring that beautiful bathhouse

Just back from a rain-drenched walk around my house, your story and sunny photos helped me get dry.