The Iris 欄

Sumiyoshi was quieter, a gentler suburb where high on every lamppost there was a sign with a flower on it. Streams rippled in neat channels among pink and marble decorative paving and large greenhouses were wedged between apartment blocks.

Research uncovered that the flower symbol was actually a Rabbit-Eared Iris (kakitsubata - 燕子花), this floppy-eared flower loves damp areas. Sumiyoshi isn’t very damp now, but as recently as 100 years ago the area was dotted with water pump windmills like the American Mid-West, all of them desperately trying to suck the marsh dry. The result was productive land, and the sea has been moved another kilometre west. But the irises went with the marsh, to continue only on in symbol form on streetlamps and in real form in tiny tucked-away streams in back-streets.

欄

I edged around the back of the wedding photo group. The bride stood with her pearlescent shell-like hood, her face frozen in white and a mini-Joker smile of red, a shade darker than the vermillion paint on the arched bridge on which she was standing. The husband poised silently, feet apart, and pointed his closed fan as if at an unseen bird in the trees. And the guests cooed and laughed and joked.

It was a relief to find shade under the sweet-smelling pines. I found a tree-stump and sat down, watching the people wander through the shrine, a suited couple with their equally smartly-dressed daughter, schoolchildren, and an elderly man who eyed the tree-stumps but limped on in search of better seating.

You can no longer hear, or even smell, the sea here. But it was not always so: until Naniwa port was constructed, Suminoe no Tsu, Japan’s oldest international port, was located just to the south of the shrine. From this port Japanese envoys travelled to China to meet representatives of the Sui and Tang dynasties. Before departure the envoys would seek the blessing of Sumiyoshi Daijin, the god of the sea.

It is a very ancient shrine, a taisha Shrine, one of the most important, and was built prior to the influence of Buddhist architecture around 211 CE. The three Sumiyoshi kami, who in ancient Shinto myth helped to create Japan, are enshrined here.

Sumiyoshi, like Tennoji, was important for the ruling class – the god of the sea would help protect the nascent Japanese state from overseas invaders. It was also connected to the god of poetry, and so upper-class pilgrims would stop here to offer their waka poems to the deities enshrined here.

I left the shrine as the sun was falling over the unseen Inland Sea, turning the light a deep faint yellow, and giving the string of shops along the approach road to the steel-truss bridge over the Yamato the warm but slightly dilapidated air of a Mediterranean town. I crossed the Yamato, but this was a new section dug three hundred years ago, so it isn’t the real Yamato that gives its name to the kingdom and battleship of yore. Beyond this new riparian cut lies the city of Sakai, once a self-governing city of merchants, but now a suburb of Osaka.

On the other side of the Yamato I walked along a traffic-filled highway flanked with the metal-box shops and restaurants with their multi-coloured, multi-shaped signs that make these kind of places look like a squashed-up version of an American strip mall. Eventually, I made it to the centre of Sakai and collapsed in the corner of a coffee-shop and sprawled my legs out to give my aching feet a rest, while I ate a crepe filled with the chocolate and cream that would give me the energy to make it home.

The World 世界The Chinese character (kanji) for the city of Sakai (堺)looks an awful lot like that for world. This would be an appropriate, if incorrect reading: it was a trading port, and it was through this port that many things were introduced to Japan. Incense arrived from China in the late sixteenth century and the cheaper raw materials in Sakai led to the development of a large incense industry in the city. The kanji may have more to do with the fact that the city was once surrounded by a moat, as the character generally indicates a boundary, or possibly that it lies at the meeting point of the boundaries of three ancient provinces. To the south of Sakai there is a hill whose name literally translates as ‘Three Countries Hill’ (Mikunigaoka — 三国ヶ丘).

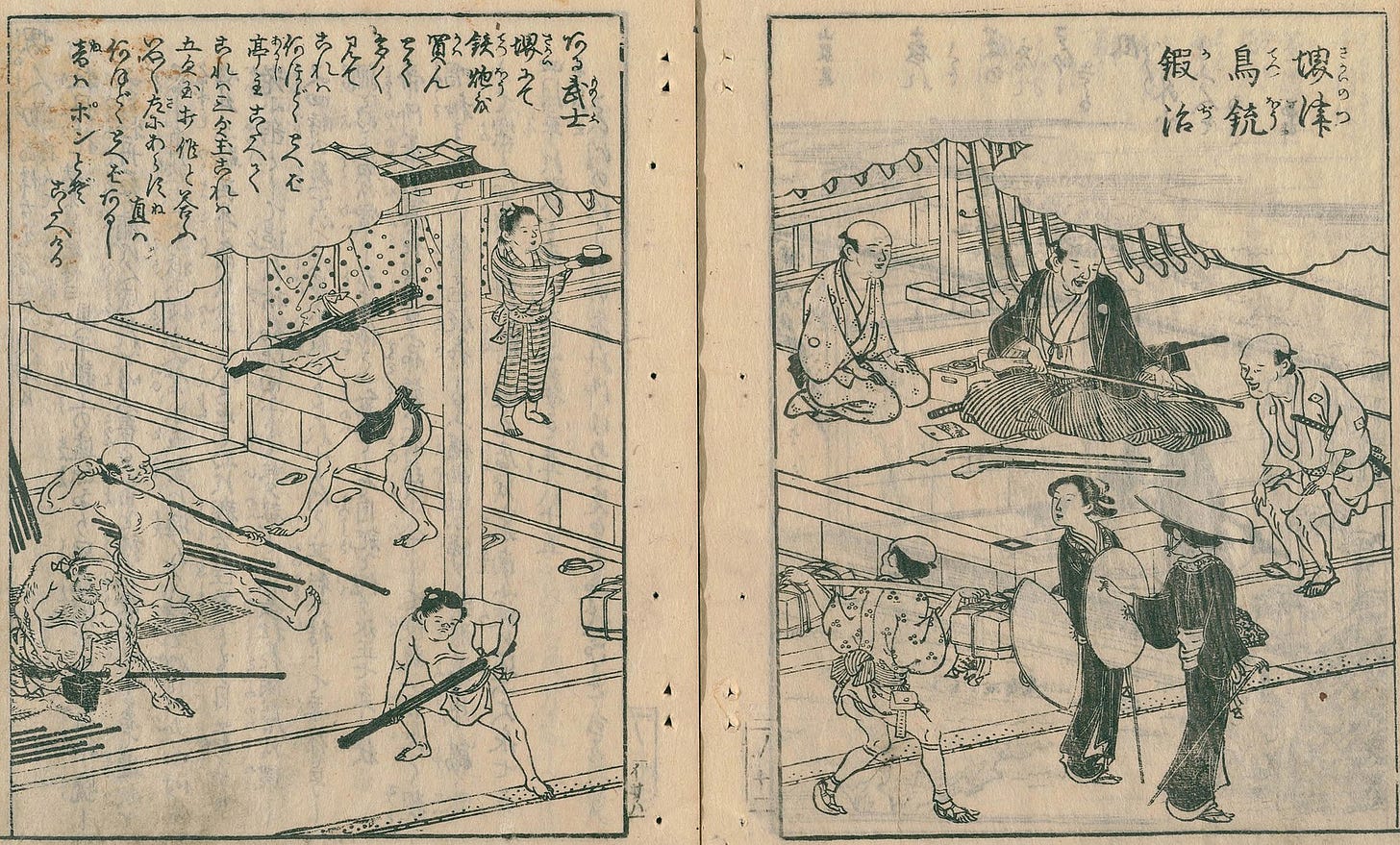

In the late fifteenth Century the rival warlords of the Western and Eastern Alliances battled for control of Japan. With war, less benign influences arrived — Sakai became an important port for importing guns. The city’s metalworkers became adept at the manufacture and repair of firearms, copying and improving their techniques through necessity. Gunsmiths sprouted across the city and before long it had become Japan’s most important gun producing location.

世界I was back in Sakai in the heat of early summer searching for an oji. Pilgrims to Kumano needed not only physical sustenance from the hostelries that lined the route, but also spiritual sustenance from a series of small shrines along the way. This oji is known as the border oji, possibly because it lies on the boundaries of the ancient provinces of Settsu, Kawachi and Izumi. Around the back of the high walls and water towers of the Osaka Detention Centre, the oji site was now merely a small set of gardens and a marker stone. Fittingly, for an area that had once been a graveyard, there was a large beetle carcass lying in the middle of the path to the stone. Pine trees wafted hot, resin-laden air across the baking street as I studied the smoothly carved rock. A marker stone is after all just a stone with some marks on it, so I rapidly moved on.

I took a detour sideways from the Kumano Kodo along another ancient route: the Takenouchi ancient road. From 613 CE this road was opened as an official road to Nara. Tradesmen with carts laden with grain from the Nara plain strained for the coastal towns and markets of Osaka Bay. Royal messengers on swift-footed horses would use the route to reach the temporary capital at Naniwa and the ships bound for distant kingdoms in China and Korea.

This detour was for a good purpose – I wanted to see the largest kofun burial mound in Japan. The kofun burial mounds are a series of keyhole-shaped mounds scattered across Japan. Often they were used to bury members of the nobility between the third and seventh centuries CE. This particular burial mound I was aiming for is believed to have been created for the Emperor Nintoku and was built during the fifth century CE. To reach this enormous tumulus, over twenty-eight metres high and four-hundred and eighty-six metres long, I first had to pass by a series of smaller tumuli, beginning with the Hanzeiryo Tumulus.

I found the Hanzeiryo Tumulus through the grounds of an attractive little shrine. As I made my way round the tumulus, I realised I was not going to be able to get any closer or walk on the mound itself. It was fenced off and surrounded by a moat. Later, as I read up on the burial mounds at home, I would discover that they were considered sacred ground and were therefore off-limits to the public. Usually, a shrine is constructed facing the burial mound, but nobody crosses the moat to the mound itself.

Threading my way through the streets of Sakai, I passed two more small tumuli and my first ancient road sign (the road was ancient, not the sign). The sign gave me some satisfaction – I was on an ancient road! OK, it was the wrong road, this was the Nishi-Koya Ancient Road which leads to the Kumano area by a more westerly route, but nevertheless it was the Kumano Kodo.

Circling the impressively large Nintoku Tumulus around the northern edge, where the moat was stagnant with pea-green algae and stray kittens played on the path, I found a sign which changed the way I viewed the mound. I had been thinking of the burial mounds as having a round head, with the wedge-shaped part of the keyhole shape being the foot. The sign told me the opposite was true, the wedge-shaped section was the head, and the round part was the foot. I had to realign my whole thinking; it was no longer a keyhole shape, but an upside-down keyhole shape.

All pilgrims passing on their way to the shrine must have been aware of this enormous tumulus; it would have towered over the surrounding area until the recent arrival of reinforced-concrete buildings. But, it is unlikely the Fujiwaras and early emperors would have gone out of their way to visit it — association with death would have brought bad luck.

The tumulus would have been a construction project on a par with the great pyramids in Egypt. A huge earth mound containing the burial chamber was constructed, drawing huge amounts of labour away from the fields, separating husbands from their wives and fathers from their children. This carefully-shaped and aligned mound was then covered with stones and crowned with haniwa pottery. For centuries it must have been an impressive sight for foreign dignitaries arriving at the nearby ports of Sakai and Sumiyoshi.

Like the pyramids, the key to understanding the Nintoku Tumulus is power. To organise labour on such an immense scale takes impressive amounts of power and influence. The tumuli themselves also demonstrated the power of the emperor who would be buried inside. That demonstration would not cease with their death, and helped reinforce the power of their successors. Tumuli only really make sense with a hereditary system of power transferral.

The Nintoku Tumulus is actually surrounded by three moats, so what I presumed to be the tumulus itself, was actually just an intermediate strip of land separating two of the moats. In fact it was hard to see the tumulus until I reached the southern edge, where a viewing platform had been constructed.

Beyond the southern edge of the tumulus was a visitor centre, and thankfully, connected to that was a cafe. Perfect, I needed both information and food. The visitor centre staff were very helpful. They became excited when I told them I was walking the Kumano Kodo.

‘Were you on television?’ one of the ladies asked.

I had to disappoint her by informing her that no, I hadn’t been on television. Then it dawned on me, they thought I was Brad Towle! I had read about Brad Towle in an English-language magazine article in which he talked about the Kumano Kodo and working as a tourism officer in Tanabe in Wakayama Prefecture. He had also recently been on TV explaining his work as the only foreigner working in a tourist office in Japan.

I let the staff know that I wasn’t Brad Towle, but I did work in Tanabe. My brief period of super-stardom was over. But I wasn’t disappointed for long as the staff gave me piles of pamphlets and information on Sakai that would help to fill the large gaps in my knowledge of the area.

Filled with a renewed sense of purpose, I went in to the next-door cafe. While I was eating, one of the visitor centre staff, a Mr. Nakayama asked if he could sit and talk to me. It turned out that he had been to England. Not only had he been to England, but he had been to Manchester. I was impressed; many Japanese tourists rarely get beyond London. Then he told me it had been a business trip to a place near Manchester, for a pharmaceutical company. This was even more exciting!

‘What was the name of the place you visited?’

He couldn’t remember, but slowly it came back to him. ‘Chapel… something Chapel, Holmes Chapel.’

Holmes Chapel! My very own hometown, the village where I grew up! My mood went from good to fantastic. What were the chances? Somebody I had met in Japan had been to tiny little Holmes Chapel.

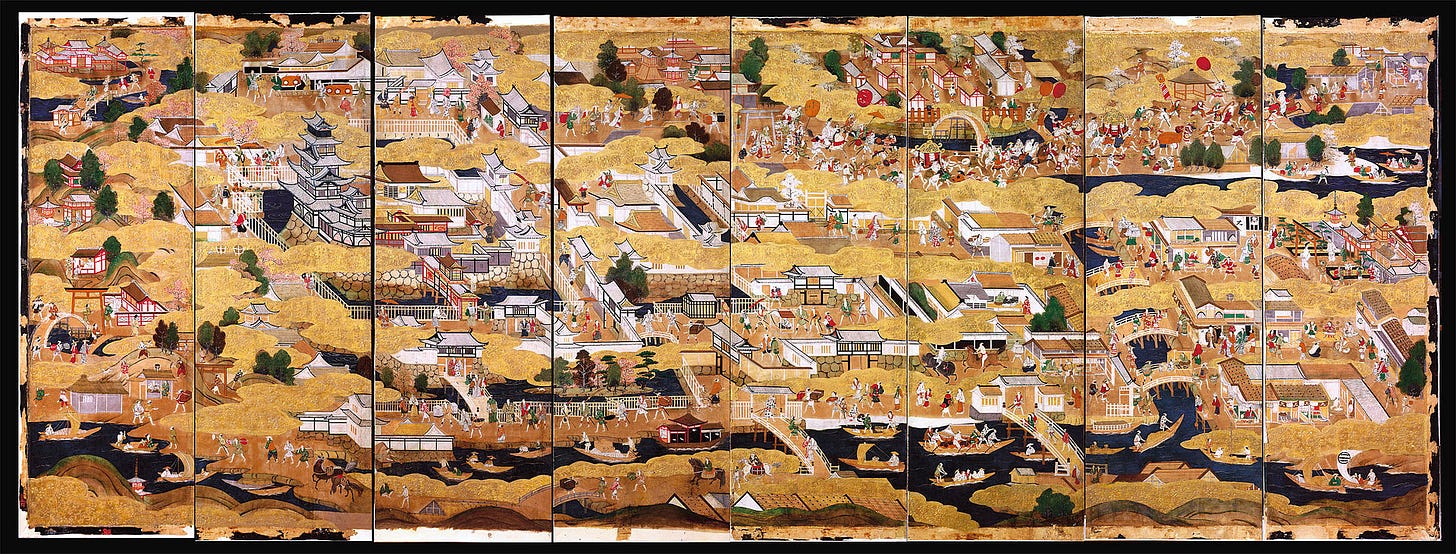

With a heart made lighter by the realisation that the world is indeed a very small place, I crossed the road to the Sakai City Museum. The museum was small, but the entrance was cheap. There were glass cases full of pottery unearthed from tumuli and archaeological digs in the Sakai area. There were clay figurines and models of horses. Better than this though, was a large model of old Sakai.

It is a belief of mine that all museums should have at least one good model. I can look at a model for hours, admiring the detail and discovering things about old towns that writing and objects in glass cases can never convey. This model was no exception. I was struck by the three different kinds of roofs on the houses. Some had clay tiles, some neat small wooden tiles like an Alpine house and others had rough wooden tiles held down with rocks and a lattice of bamboo. Presumably the clay tiles were for the wealthiest inhabitants and the rough wooden tiles for the poorest inhabitants.

A map in the museum showed how Europeans who visited Sakai in the eighteenth century viewed it. It was called ‘The Amsterdam of the East’, and not merely because of its port and network of canals but also for the size of its merchant class. In Amsterdam the merchants helped finance gloomy paintings, in Sakai they helped to finance the construction of temples and tea-houses. Sen-no-Rikyu was born in Sakai and became a tea ceremony master. He instructed the warlords Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi and developed the Wabi-cha school of tea ceremony. Wabi is a concept of simple and subdued aesthetics that still finds its way into Japanese design to this day. Many Japanese like the Kinkakuji shrine in Kyoto over the more famous Ginkakuji. Ginkakuji is seen as too ornate, so many prefer the subdued plain wood of the Kinkakuji shrine.

The best thing in the museum, however, I did not discover until I was about to leave. A large black and white aerial photograph covered part of one wall. For some reason parts of the photo were scribbled over in black pen. At first I thought they were trying to hide things in the photo. Then, as I studied the areas that had been scribbled over, it clicked. They were not hiding things, they were highlighting them. The photo was probably from an American bomber, possibly a B-29 Superfortress, and the highlighted areas were the targets.

What was even more impressive about the photo was the lack of buildings shown in it. Huge areas were open paddy field; the ‘city’ in south Osaka where I had been living previously was merely a small village. The coastal area, now a huge industrial zone looked like an idyllic Pacific island beach. Between 1942 and the present, a huge amount of residential and industrial area had been created. The photos on the wall surrounding the aerial photo showed in more detail the pace of the construction. In the pictures shot in 1960, the Sakai area still looks very rural, but by the 1970s, Sakai had become the urban suburb of Osaka you see today. It’s an impressive transformation, and it explained the strange anomaly of the single lone paddy field near my former house surrounded by a sea of housing. In the rush for growth during the 1960s and 70s, one farmer must have held out against selling their land. By the time the building boom was over, their field remained as an oasis-like reminder of the old Sakai.

In the park next to the museum there are two old tea houses, they serve as a reminder of a time when Sakai’s philanthropic merchants could patronise the tea masters and their ceremonies and houses. The unusual thing about these tea houses is that neither of them were built in their present location. The Shin-An tea house was constructed in a park in Tokyo and moved to its current position in 1980. The Obai-An (Ripe Plum) tea house started life in Nara, was moved to Kanagawa Prefecture in 1948, and then finally relocated to Sakai in 1980. This would be a recurring theme of my walk, many of the shrines and ojis along the route had been moved, sometimes several times. With their simple wooden structure, I supposed it was easy to number and reassemble Japanese buildings. The task of numbering and relocating each brick on an English building must be a more difficult task in comparison.

Your dispatches are getting better and better.

Sumiyoshi Taisha was one of the highlights of my recent trip to Osaka.

Nice blog! Well done.