The River and the Origins

Walking the Kumano Kodo Kii-ji route from Toba Imperial Villa to Yodo

Unfortunately, I haven’t had time to go hiking any more rivers around Kobe for a few weeks, so I thought it was time to break out my journal of the first long distance hike I did in Japan — the Kumano Kodo Kii-ji route. This walk is from 2008, just as the global financial crisis hit, and my Japanese was still terrible (the two aren’t connected, but I felt they were important to point out as background for the walk). I can’t find any photos for this walk, although surely I must have taken some, so we’ll have to make do with what’s available from Wikipedia and Google Earth.

When people say they’ve “done the Kumano Kodo”, what they usually mean is they’ve walked a small section near to Hongu Shrine, deep in the mountains of the Kii peninsula. Some, more intrepid people, walk from the Osaka-Wakayama border where the Kii-ji route begins to get more scenically interesting. Other, smugger people, walk the whole route from Kyoto all the way to the Hongu Shrine, and can truly say they’ve “done the Kumano Kodo”.

Along the way, I’ll try to interweave the stories of other travellers along the Kii-ji route, from the origins of the pilgrimage trail in the 1000s, all the way to the tail end of the Bakufu period in the early 1800s.

The Beginning 始まり

It was third time lucky for Fujiwara Munetada, Minister of the Right. Twice, the pollution of death had postponed his departure for the three great shrines at Kumano. The first time the purification had been defiled by the death of a dog near the building where he was making preparations for his trip. Then, in the September of 1109, his uncle had died, so once again Munetada had to begin the week-long purification rites that preceded the pilgrimage.

Munetada had started his trip while the weather was still warm and the rice was being harvested. But I had chosen a late-winter day with a cold breeze that sent the shrine maiden’s crimson skirt flapping. She smiled at me. I smiled back. She hurried on, the arms in her white hakama clasped protectively in front of her.

Ogin probably didn’t stop here though; the geisha would surely have been too pressed, too hurried, despite the length and the dangers of the journey ahead. Her lover, Toyonojo, was far ahead of her, almost back at his hometown of Doyukawa near the Kumano sanzan. It was 1816 when she began her trip, and the pilgrimage route to the three grand shrines of Hongu, Nachi and Hayatama that make up the Kumano pilgrimage site no longer held the attraction they had after Munetada had set sail. Then, such were the numbers of pilgrims, they had been likened to a column of ants.

Besides, for Ogin, it wasn’t a pilgrimage; she probably sailed straight from the centre of Kyoto on one of the traders’ boats and slipped past here with barely a glance. But perhaps she should have stopped: the wooden sign, next to the flapping leaves of the laurel hedge said there was ‘a deep belief in the god of direction, construction and safe travel living in this shrine’.

But in 1090, the Emperor Horikawa sailed for Naniwatsu with a much grander send-off. The imperial barge fluttered with pennants, poems were read and the courtly ladies in their silk finery waved him off with the most elegant of royal waves.

This was the first pilgrimage to Kumano from Kyoto. The royal example set a trend: first the nobility, especially members of the powerful Fujiwara clan like Munetada, then it filtered down the social scale until, after 200 years, the pilgrimage became popular with all who could afford to spend time away from their land, and many who couldn’t.

Just a few years after his abdication, the former Emperor Shirakawa chose this site, Tobadono, as the official starting point for pilgrimages to the Kumano shrines. Then, it was a sprawling imperial palace surrounded by peaceful willow-shrouded lakes next to the Kamo River. Now, I left Tobadono Imperial Villa Site Park, which stands where the Tobadono stood, to find the river and was confronted with a stream of belching trucks banked by ever-present vending machines and overhung with high-level traffic lights. The remains of Tobadono (the imperial state villa) are marked by a stone and a pond in the park.

The Origins 起源

At the beginning of time, not long after the gods Izanagi and Izanami had given birth to the eight islands of Japan, the god Susa-no-O scattered the seeds that would plant life across the still-desolate islands. He ranged north and south, scattering the seeds carefully and evenly. The islands were neatly covered but Susa-n- O found he still had plenty of seeds left over. He pondered for a while before tipping the remaining seeds onto a rocky peninsula that separated a sheltered inland sea from the vastness of the eastern ocean. Over time, as humans populated the islands, they developed the language to describe the landscape of the peninsula, and one word described it better than any other — ki meaning tree.

This land of trees, so heavily cloaked, would surely confine the spirits of gods who chose to alight there. And the humans had a word to describe this confinement too: kuma. Thus the tree-covered place filled with powerful spirits and mists that clung to the mountains in swirling clouds of mystery became a prime location for rediscovering the godly.

Worship at the Kumano sanzan on Kii peninsula started well before the eleventh century, but it was the visits of the emperors from Kyoto that would really begin making this pilgrimage one of the most popular in the land. The route they took from Kyoto became known as the Kii road — Kii-ji. But there were many different routes, some from Nara and some that started from the mountain temples at Yoshino and Koyasan, collectively these were known as Kumano Kodo (Kumano Old Road).

The River 川

The riverside had a strangely English air: dandelions, knotweed and dock plants grew amidst allotments of cabbages, onions and potatoes in the fine dark tilth of the flood plain. The steep saw-tooth edges of the distant mountains were the only reminder that this was, geologically speaking, a much younger country.

This was a surprising thing to me about Japan. The last country I had visited before coming here was India. When I arrived in India I was assaulted by sights, sounds and smells that were so completely alien that I could be in no doubt I was in a foreign land. When I arrived in Japan, I emerged in the open air for the first time to be greeted by sparrows and swallows and no alien smells attacked my anglicised nostrils. Yet the land was even more distant than India — so much for the mysterious orient.

Clouds like freshly-dug cauliflower billowed overhead and the breeze tugged at the willow branches setting them rustling. Every so often I came across a large water or sewage pipe, crowned with a protective skeletal fan, jutting horizontally from the gridded concrete embankment. There were signs up on the embankment that showed how far it was from the last bridge, and how far to the next bridge. But there were no signs to indicate that this had once been a pilgrimage route. It wasn’t surprising really, nearly all pilgrims would have taken a boat along this part of the journey, the Kii road didn’t really begin until Osaka.

The first I knew of the Kii road was a hand-drawn map in The Daily Yomiuri, the English Language edition of Japan’s largest circulating newspaper the Yomiuri Shinbun. The line connected where I lived in Osaka with where I worked in Wakayama City. It looked like it went right past my house.

But first I had to find out where exactly it went. An internet search in English brought up nothing. So it was time to use my limited Japanese; I mistakenly thought the “ji” character in “Kii-ji” was the Chinese character for road. In fact it was a different character meaning route. I had therefore unwittingly limited my web search results, but come across an extremely informative website showing the Kii-ji route to the Kumano sanzan. Extremely informative that was if I could understand the Japanese — I couldn’t (and this was in the days before good quality internet translations).

But it did have maps, I didn’t need Japanese to understand where I was on a map, I could see where Kii-ji started and how it really did go right past my house. And so now I found myself on a cool February Sunday morning on the Kamo riverbank beginning to retrace the Kii-ji.

The Kamo River merges first with the Katsura, the two big rivers in a Y shape that form the core of modern Kyoto. Then, with the Uji River from southern Kyoto, the heavily-sandbanked Kizu River joins to swell the Katsura into the Yodo River, which I will follow all the way to Osaka.

The riverside path became popular with cyclists, figures in bollock-hugging Lycra whizzed past as I went by Kyoto’s horse-racing circuit and a series of golf-courses. I had considered taking a bicycle to ride this part of the journey; I thought it would give me a more appropriately boat-like speed. But although the trains in Japan are very good, and cycling is very easy, combining the two is very difficult. There are bicycle parks at the stations, and lots of people ride bicycles, but taking bicycles on the train is impossible unless you have a folding bike.

I asked people if there were river cruises down the Yodo River to Osaka. They looked doubtful, and with good reason, for when I saw the Yodo River I realised there were no boats. So boats and bicycles were ruled out. I had no choice but to walk.

On the opposite side of the river lay the capital that never was. In 784 the Emperor Kanmu had decided to move the capital to a new site from Heijoukyou (present day Nara). But the move proved to be inauspicious: one of the Emperor’s closest associates, Fujiwara Tanetsugu, was assassinated during the construction of the new capital. One of those accused of plotting Fujiwara’s death was the Emperor’s younger brother – Prince Sawara. The prince would protest his innocence, but soon after he would die on Awaji Island in the Inland Sea. The Emperor, haunted by visions of Sawara’s ghost (although he apparently had nothing to do with Sawara’s death) decided on yet another change of location for the capital, this time to Heian (now Kyoto), located just to the south of Lake Biwa and at the meeting point of two rivers that fed the Yodo River.

His second choice of capital was definitely better than his first; it would remain the capital until the emergence of Edo (now Tokyo) as the pre-eminent city eight-hundred years later.

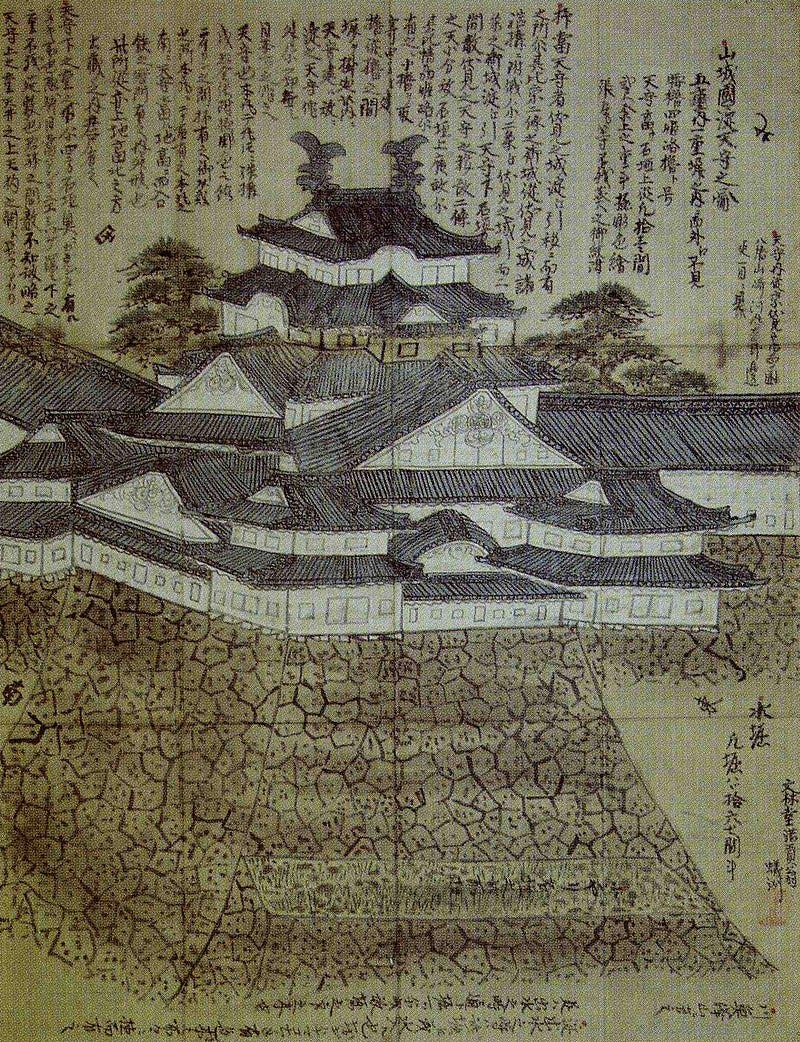

Before taking the train back to Osaka, I had time to wander the ruins of Yodo Castle. Situated at the confluence of so many important rivers, it guarded the commercial centre that collected the tributes from western provinces of Japan as well as a lot of salt from places like Okayama (see my previous walk around the Inland Sea). The castle was burned down by a lightning strike in 1756 and were never reconstructed. All that remains now are the outer walls and part of the moat.