Where Time Meets the Sea

From Mineyama to Amino along the Japan Standard Time Line

I awoke to sunlight pouring through the crack between the window shutters. I felt well-rested, ready for another day of walking. I could see from the map, I didn’t have too far to go to reach the coast again and there were no significant mountains to cross. So, I took my time getting up, it was past nine o’clock by the time I left the hotel, and after I stopped for a conbini breakfast, it was getting on for ten.

The broad flat fields around Mineyama were quickly throttled by clusters of mountains. Beyond the Pompidou-Centre styling of Mineyama’s small train station, one narrow straight valley cut through these mountains to the coast. Plenty of farmers were out tending to drainage channels and weeding crops. On one side of the road, the mountainside met the road in a sandy bank covered with a screen of thick grass. What could be lurking there? I tried to walk on the other side of the road, but a series of passing cars forced me back to the waiting jungle.

Once in a while a passing one-car train click-clacked its way to or from the coast. The sun shone on the glimmering mud of freshly-flooded rice paddy and the gleaming grey tiles of old village houses. I stopped to read the signboard about an ancient tomb, perched on a verge, avoiding the stares and gaping-mouths of passing car passengers.

The Akasaka Imai Tomb is a large rectangular burial mound built in the Yayoi Era - late 200 to early 300 CE. Traces of post-holes indicate a line of poles behind the grave site. The earthenware and headware and ear decorations found here show strong links with both areas on the east coast of Japan and across the sea in ancient China. At first glance, I thought the picture of the remains of the headware and ear decorations showed blood, but then I realised it was merely the red colour of the underlying rock, perhaps why this site was chosen. Akasaka means red slope.

The valley flicked out the railway line and road into a broadening delta of square fields and curving rivers. Just as it did this, I noticed a sign pointing to the Kyotango History Museum. Would it be open? Google Maps showed it was. I had plenty of time, so why not visit?

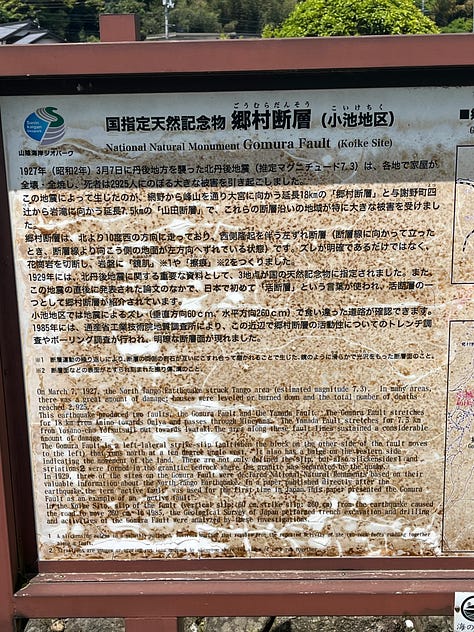

The road to the museum was strangely kinked, and a signboard at the point of the kink explained why - the road had been moved by the North Tango earthquake of 1927. The destruction was vast - almost every house in Mineyama had been flattened in the magnitude seven quake. Nearly three thousand people were killed and nearly eight thousand injured. The slip movement of the fault tore a great rent in the earth and moved the road 260cm. A sign on the other side of the road announced the construction of a landing pad for the Doctor-Heli air ambulance.

The museum itself looked like a 1980s elementary school, with a typical connected gymnasium building. The car park was empty, only sparrows chattered in the bushes. I was beginning to think the museum was actually closed, but when I pushed on the door, it opened and an old lady came out to greet me. I pushed my feet into several-sizes-too-small shiny brown slippers, paid my fee and followed the signs around the museum.

I was the only visitor, and quite probably the only visitor that day, or perhaps even that week. There was something of the Japanese horror film about the place - the stillness broken only by the ping-bing of dying fluorescent lights. There were exhibits on the local towns’ main industry - silk. There were various agricultural implements used before the arrival of the piston engine. There was a recreation of a Japanese schoolroom. The creepy feeling wasn’t helped by the cover of a magazine in a glass case in the corner of the schoolroom from World War Two, depicting an Imperial Japanese Army soldier standing on the wing of a downed British aircraft.

When I left the museum, the old lady at the entrance was asleep, head down on a desk. I closed the door quietly, so as not to wake her.

I followed the river as best I could toward the sea. When I finally caught a glimpse of the dark blue waters of the Sea of Japan framed between two mountains and a stone torii gate, there was something of the frisson of excitement from childhood of seeing the sea for the first time on a car journey, cresting the Lincolnshire Wolds or the Welsh mountains. It was strange, because I had just seen the sea the day before at Miyazu. But the sea here was open, with no further obstructions until it reached the Korean coast, and the framing and the weather were perfect. There was something else too, a little sense of the excitement from Enid Blyton’s The Adventure Series, I didn’t quite know what was going to happen next and the coastline was full of rocky coves.

The monument that marks the northernmost point on the Japan Standard Time Line lies a few miles outside of the village of Amino. After stopping to eat lunch dangling my feet from a sea wall and admiring the rocky outcrops next to Amino, I toiled up the slope to find the monument. The road clung to the grassy cliffs. Down below, aquamarine seas, clotted with mats of seaweed, swirled around rough rocks. Above, tonbi (black kites) soared, swooped and screeched. Odd trees gripped the cliff face and twisted themselves upwards.

The monument was hidden among trees, a metallic thing with two solar panels and a clock. It provided good shade for me to eat more lunch, remove my socks, and figure out how I was going to get home.

I returned to Amino, not following the river this time, but using the straightest road to the station. There, in the coolness of the ticket office another foreigner was trying to buy his father tickets to return to Kyoto the next day. The station master started the process of making the reservations and tickets, and asked the foreigner to sit and wait a while.

I went up to the ticket window.

“Please wait.”

“Yes, I’ll wait.” I was in no hurry, the next train was not for another twenty minutes. Still, something was wrong. Maybe I’m getting good at reading the air (kuki o yomeru) after so long in Japan. Did the station master think I was the same foreigner as the one who was buying tickets for his father?

I loitered uncomfortably, looked for a ticket machine, and found it hidden behind a big sign saying “Please buy your tickets at the ticket window.”

Ten minutes to go until the train comes.

I return to the ticket window. The station master is still printing off tickets for the other foreigner.

Finally, the station master looks up. He starts trying to explain that he’s still printing the tickets and making reservations etc.

Then, he realises - I’m not the same foreigner!

He apologises profusely, looking flustered. I assure him it’s okay, what’s the probability that two unrelated foreigners come into a tiny rural station one after the other!? He continues apologising, but I get my ticket and make it to the train with plenty of time to spare.

Thank you for letting us come along on your exploration! I especially liked learning the expression "kuki o yomeru".