When I graduated from the Cub Scouts to the Scouts proper, I needed some uniform trousers. The colour of the trousers, somewhere between a light grey and brown, was called “mushroom”. This is the key colour of urban Japan. The pillars of the train station I left were being painted this colour, and the first building I saw out of Hoden station was also this colour. It’s a utilitarian colour. Yes, it can be unremittingly dull, but it’s there to serve a purpose — to remind everyone that the building is there to serve a purpose.

To the left, bare scrubby Mediterranean hills, gouged here and there for rock quarries. To the right, fields rotavated to tumbles of dead beige stubble and clods of earth with green grass poking through. The top clods were dried to corpse-like grey. The lower clods a dark, rich brown, promising new life. Wafts of pork and ginger came from scattered suburban houses.

I passed a golf driving range where the balls were shot into a lake. How did they get the balls back? The bottom of the lake must be a bed of golf balls. Then the road squeezed through a gap in the hills into another valley. Here, the fields were rolled to exact levelness, the soil a powder from which short clumps of grass and dead nettle poked through. These fields were ready for the next crop of rice, the JA rice processing centre conveniently located just up on the hillside. But some fields were drilled with neat rows of winter wheat or barley like those I’d just left behind in England.

I’d learned my lesson from the last walk. I had bought lunch from a convenience store in the station. I ate it with legs dangling from a concrete embankment. Karasu no endo (whistle peas), a kind of vetch, was already starting to grow in the unusually warm winter on the channel banks. The channel bottom was slick with thin streamers of weed and grey mud.

Up a highway service road over a tunnel entrance, and then I entered the forest. Few had come this way. The path was often the same as a stream. The pink ribbons that marked the way were tattered and faded. Then they disappeared altogether. The path became a wild boar trail. Their rooting marks and hoof prints were everywhere. I found a branch and used it as a walking stick, trail machete to hack at undergrowth, and a potential weapon should I meet a wild boar coming the other way. I felt like I was in Lord of the Rings.

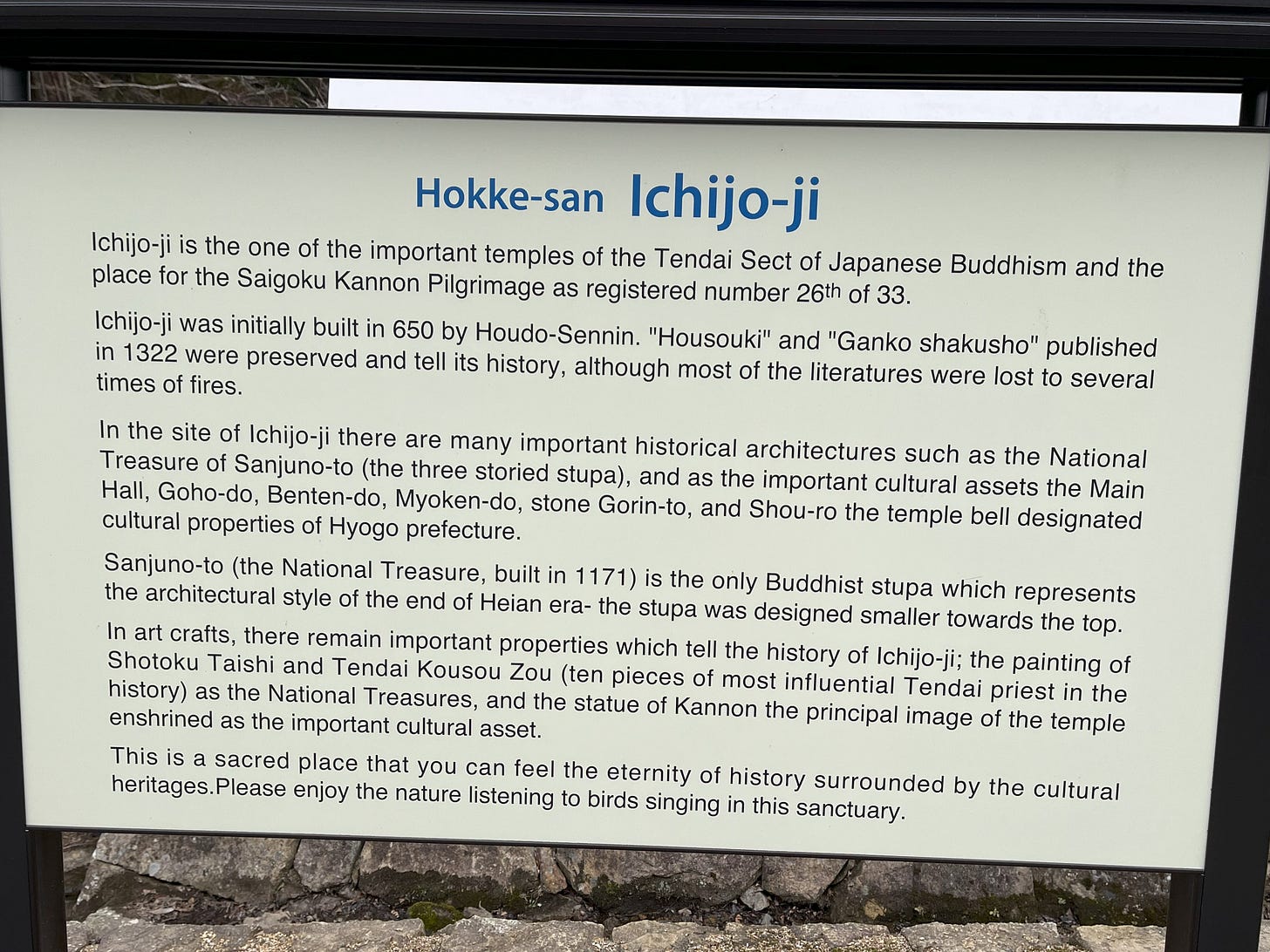

I came out of the forest at a large temple, Ichioji. One of 33 temples that make up the Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage. The 33 are scattered across prefectures from Gifu to Wakayama, so sadly there’s no single pilgrimage trail connecting them. All of them have as their main image Kannon, the bodhisatva of compassion.

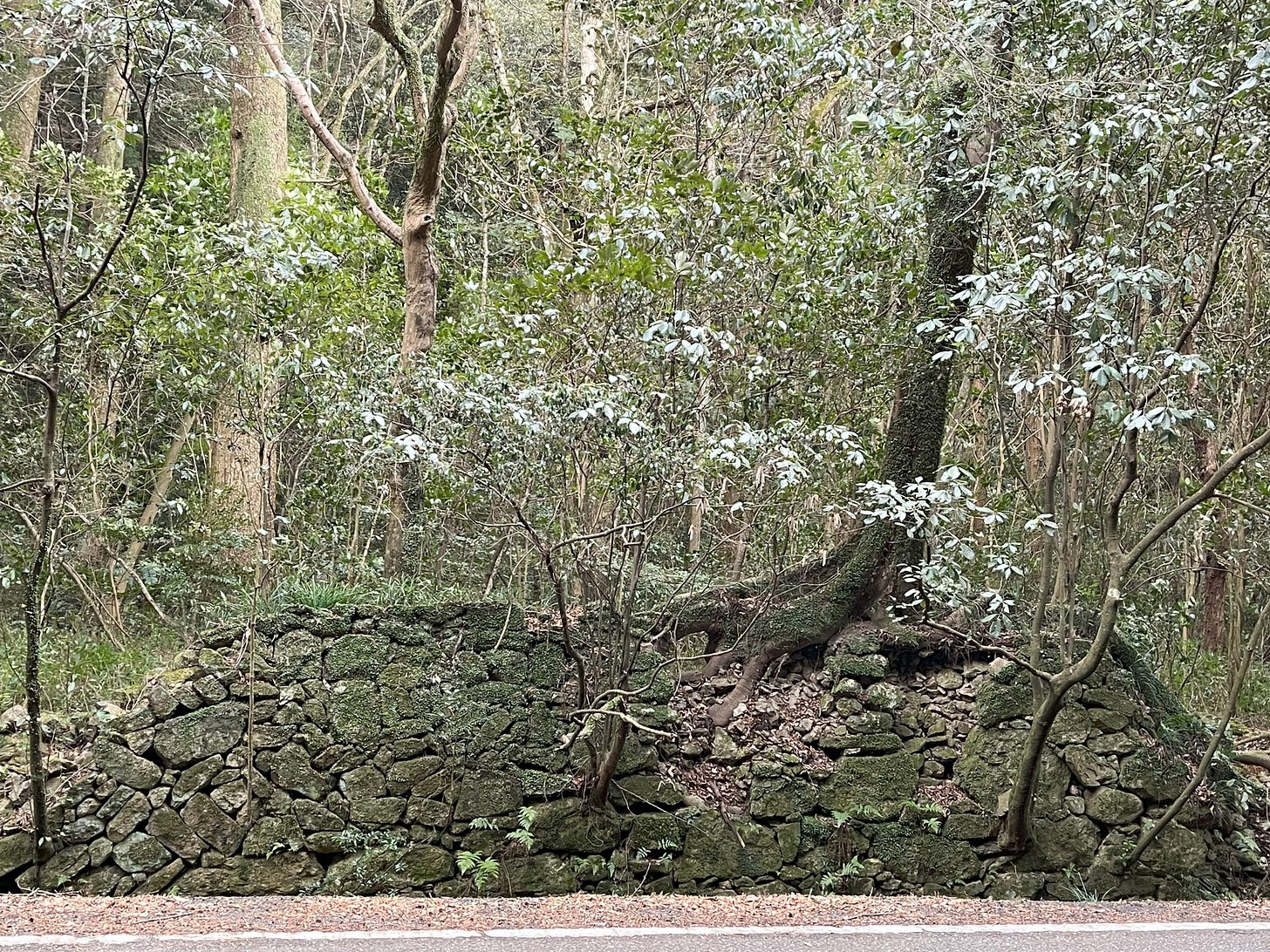

Up here in the dampness, moss grew over everything. Walls, paths, entire pavements (sidewalks) were lined with it, softening anything hard. The sun began to crack through the overcast sky as I headed down to a landscape of double-peaked hills and narrow valleys.

I passed another reservoir with an exposed muddy bottom. Then followed the edge of a highway along a service road lined with huge cattails and susuki grass. Sirens wailed, trucks howled and motorbikes roared past.

The highway rose on pillars and disappeared into another tunnel. In the peace I walked across another level valley bottom, daikon radish thrusting out of their furrows, and the first hint of deep-pink plum blossom. The sun was sinking, shadows stretching across the flatlands.

Up again, climbing past Himeji Central Park, a large safari park in the hills behind Himeji. Kento’s Law about pavements — a huge wide one on a fairly quiet road, separated from the road with box hedging and miniature pine. I enjoyed it, but why here? Were lots of people walking to the safari park? I kept an eye out for escaped lions as I passed. Down again, to the Ichi River. I relaxed. I was going to make it to the station before dark with no problem.

The view down the valley towards the coast was filled with the smokestacks of the Sanyo Metalworks. Which was appropriate, as I found the road that followed the Ichi River was one of the first modernised turnpike-style roads in Japan. The Gin-no-Bashamichi (Silver Mine Carriage Route), as it became known, led from port at Himeji to the mines of the Hyogo mountains and was planned by a French civil engineer.

Finally, my return-train town of Tohori. It had everything you expect of a rural Japanese town that’s not yet too far from a city: a long-spent love hotel, an eighties-style barber with the word split into two as “bar ber” ,a new, fashionable-looking dental clinic and right next to the station, a derelict collection of apartments.

I bet it was beautiful coming across that Temple when you left the trail. Thank you for sharing! Loved reading your story.